I recently introduced myself to a new investor as “Director of Innovation.” He looked at me like I’d just said I was a Disney Imagineer. Now, I love a good princess flick as much as anyone but I’m no Imagineer. At any other company, I’d be a director of R&D. But as the clickbaity (sorry) title says, we don’t do R&D at Expel.

At Expel we’ve consciously chosen to avoid the term “R&D” to define a team, a job role or anything else. Instead, we use words like “experiments” or … “innovation.” A lot of thought went into this decision. You see, we’re trying to challenge a lot of the standard ways managed services operate and that means we need to constantly challenge ourselves to do things in new ways and not just cut and paste processes from our past just because “we’ve always done it that way.” That includes R&D. Or, in this case, innovation.

=========================

But first … a brief disclaimer

=========================

Before I dive in though let me set the record straight on a couple things.

This blog outlines research in the field of cybersecurity. I’m sure some of the challenges I describe exist in other industries, but I don’t have the experience to talk about them in that context.

I’m personally guilty of many of the bad behaviors we’ll discuss. Expel’s approach tries to address some of the challenges I’ve both witnessed and experienced.

Finally … yes, I know not every research group has all of the challenges I’m about to outline. And … yes, I know not every researcher exhibits all the behaviors I’m about to outline. And … yes, I’m sure you and your group have none of these challenges.

What’s in a name?

Quite a bit, it turns out. Think about it. R&D defines a group of people. You either belong or you don’t. At Expel, we believe anyone can come up with a game changing idea. While some folks in the company are more focused on experimentation, we don’t want to exclude anyone. We view innovation as the constant flow of ideas from anywhere in the company to a backlog that is actioned by individuals or teams across an organization. This means that everyone with a good idea or desire should be able to participate. That’s why we choose the term innovation. Anyone can be “innovative.” But you can’t describe yourself as “research and development(y)”, especially if you’re not in the group.

There’s also a flaw baked into the name itself. Research and development defines a workflow. And, just as its name suggests, a research group does research first and then develops a solution to a problem. But too many research groups view their job as done once they’ve handed off their idea to engineering. Too often, they don’t have any skin in the game when it comes to getting that solution into production. If the solution falls apart in engineering, culturally, they aren’t encouraged to see that as a failure. Instead, they’re more likely to end up in a food fight with engineering (and possibly product management). You may recognize some of these statements:

- R&D to engineering: “You move too slow”

- R&D to engineering: “This feature is way more important than Windows X backwards compatibility!”

- Engineering to R&D: “Everything you hand us works in 10% of situations.”

- Engineering to R&D: “This isn’t engineering quality code, rewrite it.”

How to create a healthy innovation backlog

A healthy research (or innovation) backlog typically includes a bunch of tactical ideas that are being researched to solve day-to-day challenges the company faces. But we think the backlog also needs to include what we call “crazy town” ideas (sometimes called “moonshots”). These ideas probably don’t correlate to the day-to-day pains and problems your company faces. They’re forward-looking … and, as we like to say, anticipate where the puck is going (#ALLCAPS).

Having a diverse innovation backlog is critical. But when a company has a traditional R&D structure (that is, when a group is labeled “R&D”), it’s effectively telling the rest of the company, “Hey these are the people to come up with new ideas.” Flip it around and what employees can hear (or think) is, “Well, my ideas don’t matter so I won’t think critically or offer feedback.” Or, perhaps, “Well, since I’m not on the R&D team, I’m going to research over here in a corner and not tell anyone about it.” Or, worst of all, “I can’t participate in R&D so I’m going to take my ideas to another company.” Innovation is a company-wide activity. Having a backlog of ideas siloed off in R&D isn’t an effective way to tackle innovation. Read on to see how we’ve tried to approach things differently.

Three signs that your R&D team is stifling innovation

It can be hard, at first, to recognize when R&D has put up unnecessary hurdles. Nobody picks up a bullhorn and announces them. They’re more subtle and silent. Here are three signs that you’ve got them.

- There’s no single view of all research projects: No one person can identify project owners, deduplicate similar projects, track project status, etc. This lack of visibility can impact cost and engineering velocity.

- Great ideas stay hidden: New ideas that are great may never get brought up. If you’re finding employees are contributing to or creating their own open source projects that’s a possible sign your innovation is going elsewhere.

- A-ha! Engineering: Large projects stay hidden until a great big reveal, ambushing teams across the company who could have been helpful / involved.

- You’re solving irrelevant problems: Over time, your R&D group will likely move further away from relevant problems. Then, they’ll wonder why other teams aren’t bringing up new issues for them to tackle. If your R&D group is landing new projects, but the projects aren’t well received there’s a good chance they’re growing disconnected from the day-to-day challenges your company is facing. This happens all the time in security where challenges often change on a daily or weekly basis.

If any of these warning signs sound familiar you probably need to rethink your approach to how you innovate.

Building an effective innovation engine (aka what I’ve done at Expel)

I was one of the first employees at Expel, so the only thing I could do was innovate. But, as a new organization, it also gave me a unique opportunity to experiment with new cultural norms that favor innovation, reward failures and involve everyone. Here are four things we’re doing.

- Zero Day indoctrination

Expel’s culture is unique. We’re a transparent managed security provider and transparency is core to our culture. Every new employee listens to a presentation called the Expel Palimpsest. It explains the fundamental tenets of our culture. And it includes this slide.

This slide summarizes Expel’s overall approach to innovation – it involves everyone and it starts on day zero. The innovation slides are aimed at everyone – not just our security analysts or engineers.

Now, a single slide doesn’t create a culture. That comes from day-to-day reinforcement of the messages on the slide with actions. One way we reinforce that is through a weekly experiment meeting and our monthly all hands meeting.

- Weekly experimentation meeting

There are three main goals of our weekly experimentation meeting:

- Review new ideas (with a focus on prioritization). If we’re going to consider an idea for prioritization, this is where we define concrete next steps that include failure/success criteria for the first pass. It’s a delicate balance when a new idea comes in that isn’t worth actioning. We usually encourage them to think more about their idea while exposing them to alternatives to what they proposed. As you build trust, you’ll find you’re able to more directly say this is probably not worth actioning because of X Y Z.

- Update status of ongoing experiments. For experiments that are already underway we like to focus on what progress has been made, discussing ideas about how to improve them and identifying (and clearing) roadblocks that might slow it down.

- Review results from individuals or teams. When we review the results of an experiment there’s a lot of discussion. Did it fail or succeed? If it failed, do we want to try something different or call the whole experiment a failure? If it succeeded, is it still a high priority experiment?

A different person runs our weekly meeting every week. Changing up who leads it is important; it breaks up the monotony and allows individuals to focus discussion on what matters most from their perspective. Changing who runs the meeting also reinforces that innovation is democratized across the whole company. Case in point, last week one of our badass interns ran the meeting.

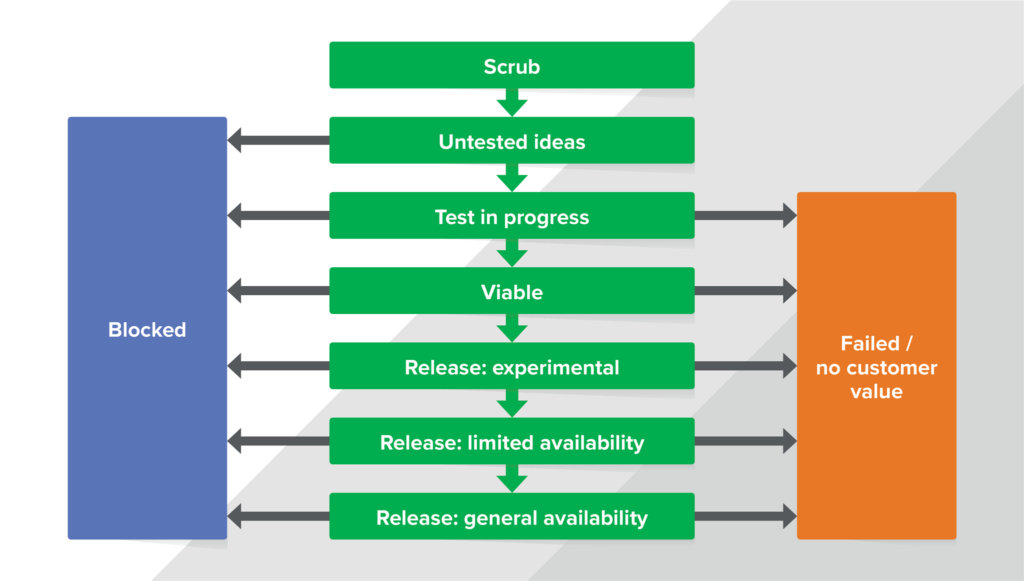

Anyone at Expel can attend the experiments meeting and any individual or team can work on a prioritized experiment. We use Trello to track our ideas as experiments. The diagram below outlines the various states an experiment can live in as it moves from concept to completion.

Phases of an experiment

An important note: These phases are specific to experiments related to detection, hunting, and response. The phase may differ if we were doing different types of experiments (for example, evaluating new database performance).

Scrub – This is where new ideas go. Every month at our company all hands we acknowledge everyone who submitted a new idea, regardless of what the outcome was.

Untested ideas – After we scrub an idea, we move it to “untested” unless we’re able to resource it immediately. We try to keep this prioritized, but “try” is the operative word there.

Test in progress – At this phase, we’ve decided to see how viable the idea is. We do our best to scope these tests so they have a quick turn around – a week or two on an initial idea is ideal (though there are exceptions). The goal here is to see if the concept holds up at some small scale.

Note: at this point and going forward any experiment/idea can move from a given phase in the workflow to either “blocked” or “failed” state. If we fail we’ll have a mini post-mortem write up about what we tried, where we failed and anything we would do differently. That way if we want to pick up a failure a year from now we can recall what happened.

Viable – If the test was successful, where success is reviewed and determined by everyone attending the weekly meeting, the experiment goes into the “viable” state. This state is the queue where engineering (or researchers with an engineering background) can go to pick up work. The queue is also another point where we prioritize. We can take resources off of other projects to move something into a release state if we think it’s that important.

Release: experimental – Once we’ve taken the viable idea and resourced it to get it quickly into production, the idea/feature/experiment is marked as “Experimental.” This means the only people reviewing the output are those involved in the experiment and possibly one customer.

Release: limited availability – At this phase, we’ve reviewed the experimental results, run the experiment on varying data types/sizes and we’re reasonably confident it’s stable, meaning the variance is limited. Once an experiment gets to this phase we’ve got our most senior analysts looking at it.

Release: general availability – Finally, when an idea becomes generally available, it means we’ve got strong documentation, monitoring, logging and support. We’ve had two or three associate analysts review it, and they were able to consistently draw the same conclusion. Associate analysts are generally analysts who are working their first security job.

- Two critical partners: internal and external customers

Our internal customers for the experiments are involved in the process from inception to delivery. Heck, it may have been their idea in the first place and they just didn’t have the dev skills to execute it. By meeting with any and all stakeholders, everyone gets an opportunity at every phase to ask questions like, ”Is this still the most important thing we should resource?” so we can continuously prioritize experiments that have (or could have) an impact. Too often, researchers go heads down for three months, come back up and the ground has shifted out from under them so that the problem they have solved no longer exists because of _______.

We also involve our customers as early as possible – even at the experimental release stage. It’s one of our core tenets. We’ll talk to the customer before we run an experiment, so they know we’re going to try something new. Then, after the experiment, we provide results even if it went poorly. While this approach works for us, you’ll have to figure out how and when you want to engage customers. We’ve found that by engaging customers early, they get the opportunity to offer feedback (which they like) and we learn things early in the process that ultimately save us time. Through these conversations, trends can emerge. You’ll know you’ve really hit the win button when customers are proactively engaging you with new ideas.

- Yay! Another failure.

If fear of failure is part of your culture it will squash creativity. You’ll always hit your target because you aren’t aiming outside your comfort zone. This is very dangerous for the longevity of any company (unless you are flush with cash and can acquire companies who don’t fear failure).

If you’re transparent about your experimental results, you naturally destigmatize the fear of failure. And when the whole company sees experimentations at all levels of the business it gets even more interesting.

The greater danger for most of us lies not in setting our aim too high and falling short; but in setting our aim too low, and achieving our mark.

– Michelangelo

As a young company that’s still growing, we want to fail fast, and failures have to be applauded. Again, we make sure that we’re walking the walk – at the highest levels. A director saying “great job failing guys that’s what we want” doesn’t have the same impact as the CEO standing up in front of the company month after month and saying “We’ve got to fail more.” The importance of celebrating failure in a company is that it removes the pressure of always being right. This pressure can swallow up impactful ideas and prevent them from being shared. Reed Hastings CEO of Netflix summarized this sentiment well:

“Our hit ratio is way too high right now,” Hastings said. “So, we’ve canceled very few shows … I’m always pushing the content team: We have to take more risk; you have to try more crazy things. Because we should have a higher cancel rate overall.”

The approach I’ve outlined here may or may not work at your company. The point is, that you should always be evaluating how you’re innovating (or R&Ding). At Expel, we’re continually trying to figure out ways to involve more people in the innovation process. A new initiative we’re starting internally is “twitch for innovation” where we set up fixed times to hold Zoom conference screen shares. The person sharing their screen talks about how they’ll work on an experiment, and actually does a bunch of the research with people watching. Anyone in the company can join the session, watch what they do, how they think and ask questions. This idea isn’t new. In fact, well-known researchers like Cody Pierce, and Silvio Cesare have been live streaming various research sessions. Being able to watch a research professional is invaluable. There’s always something to learn no matter how experienced you are. Eventually, we’d love for customers to be able to watch as well.

Conclusion

I know changing culture is hard and one meeting a week likely won’t change anything. Coming to Expel, I had the benefit of defining a new culture (vs. changing an existing one). That said, here are a few ideas that might help in your innovation journey.

- Consider over communicating research status. Go to weekly engineering planning or sprint meetings. Make sure they know what you’re working on and make it clear to engineering that nothing will get dropped in their lap. Emphasize that bringing something to production will be a collaborative effort.

- Require people responsible for experiments meet with engineering to understand code coverage and code style guidelines. Delivering your results with unit tests that meet code coverage requirements and style guidelines is a great way to show you respect engineering.

- Have engineers pair up with researchers (and vice versa). It will help each team build a healthy respect for what each other brings to the table.

- A weekly meeting to discuss new public research or internal research is a good first step to improving visibility. As you build trust, you can move to a more formal collaborative process but starting out with a meeting to discuss ideas and results is a good first step.