Current events · 2 MIN READ · HIRANYA MIR AND MILO ROMANO · DEC 7, 2023 · TAGS: Phishing

Ever heard of qishing? It’s a big deal for hackers right now. Here’s how not to get caught

In our most recent Expel Quarterly Threat Report (QTR), we talked about the recent uptick of “qishing,” a type of credential harvesting attack that uses QR codes to drive victims to malicious URLs. Not only is qishing an obfuscation technique to avoid detection with known malicious domains, but it’s also an attempt to move the attack away from typical endpoint detection.

The rise of COVID spurred an increase in the use of QR codes, so people have grown accustomed to its use by legitimate services.This presents challenges for defenders, as users scanning QR codes from their personal mobile devices unfortunately means less visibility for security and IT teams. Cyberattackers capitalized and now use these codes to gain access to credentials, personally identifiable information (PII), and credit card information.

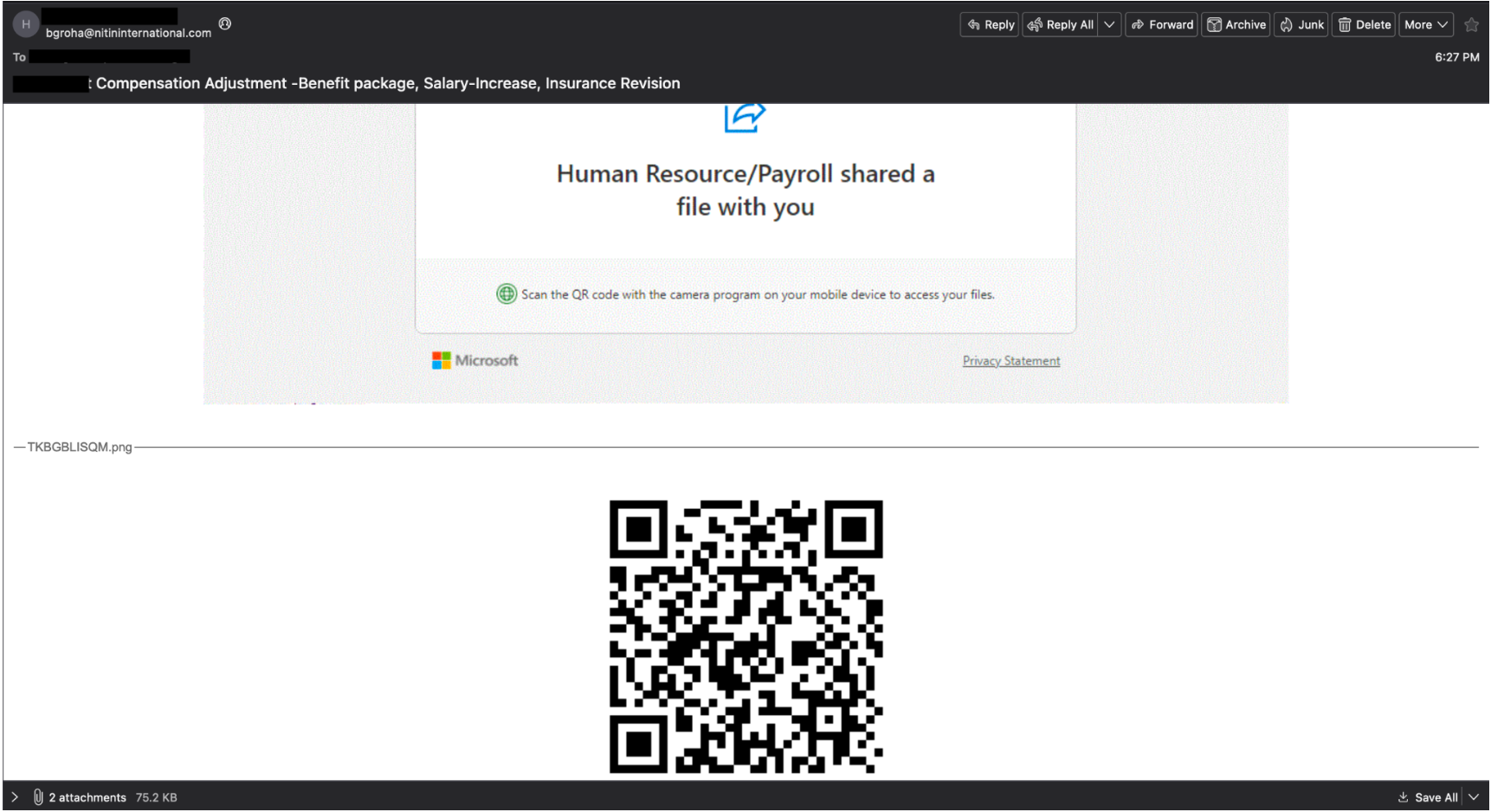

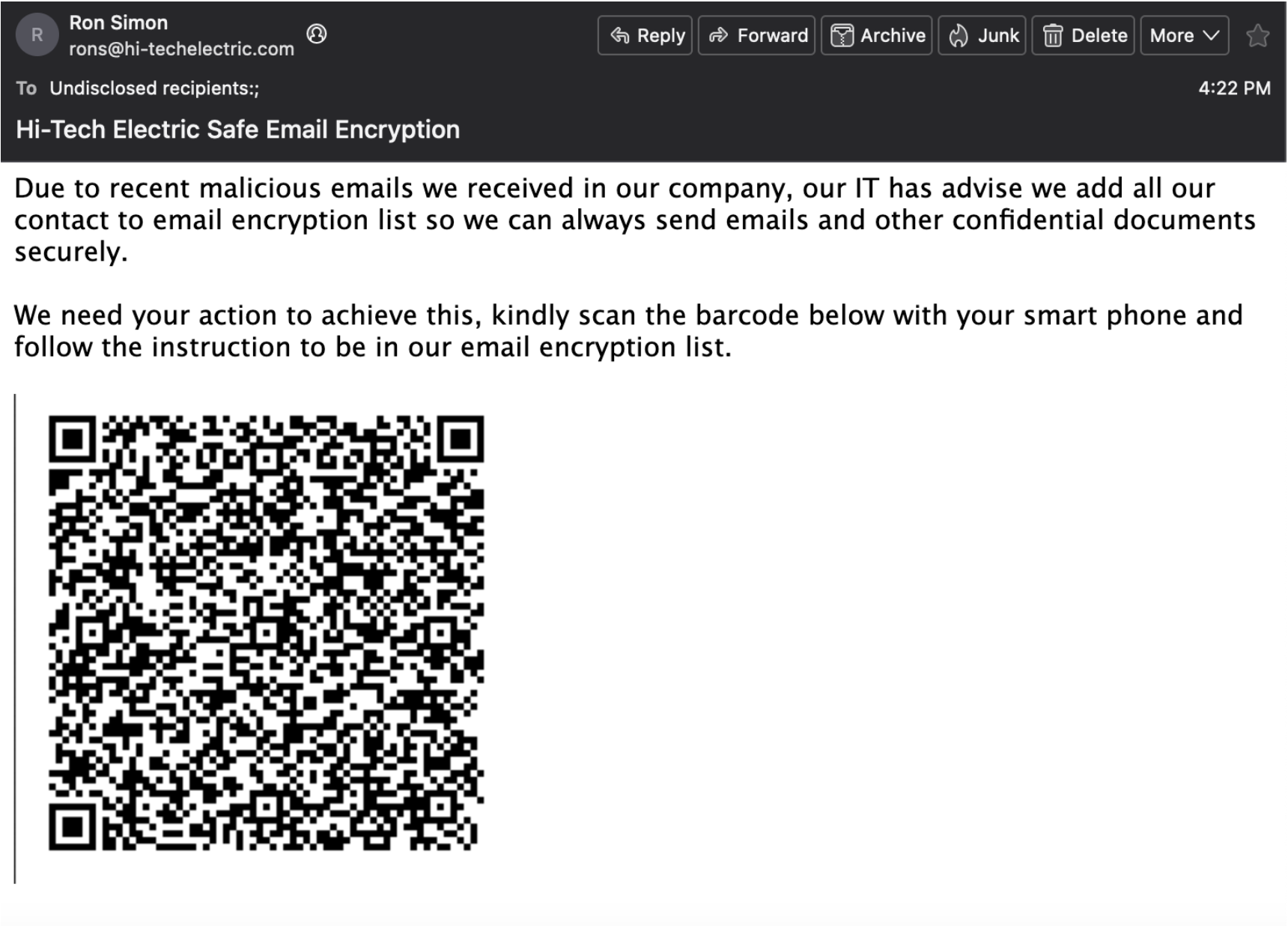

These attacks masquerade as a wide range of legit uses, including multifactor authentication requirements and fake security measures (such as new encryption technology). Here are a few examples of emails we’ve seen:

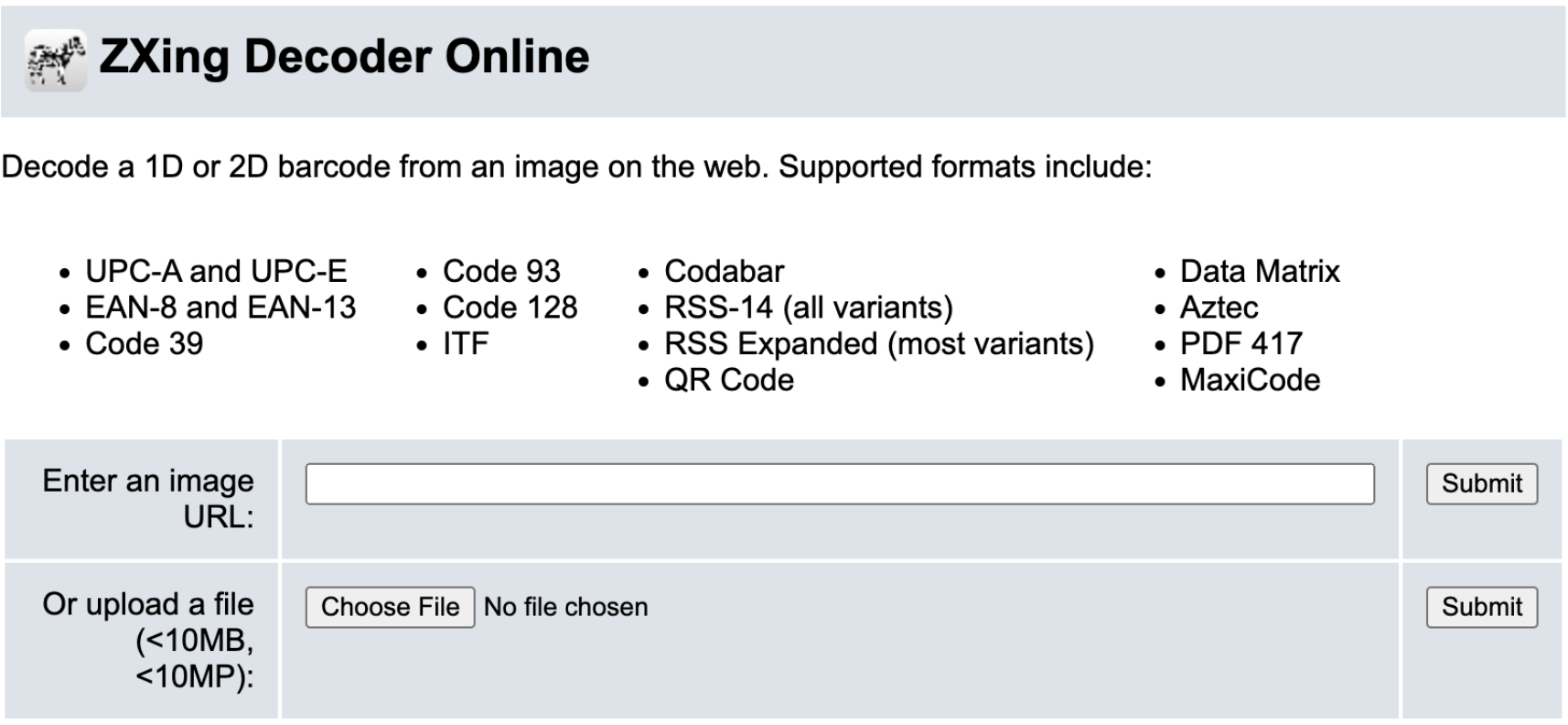

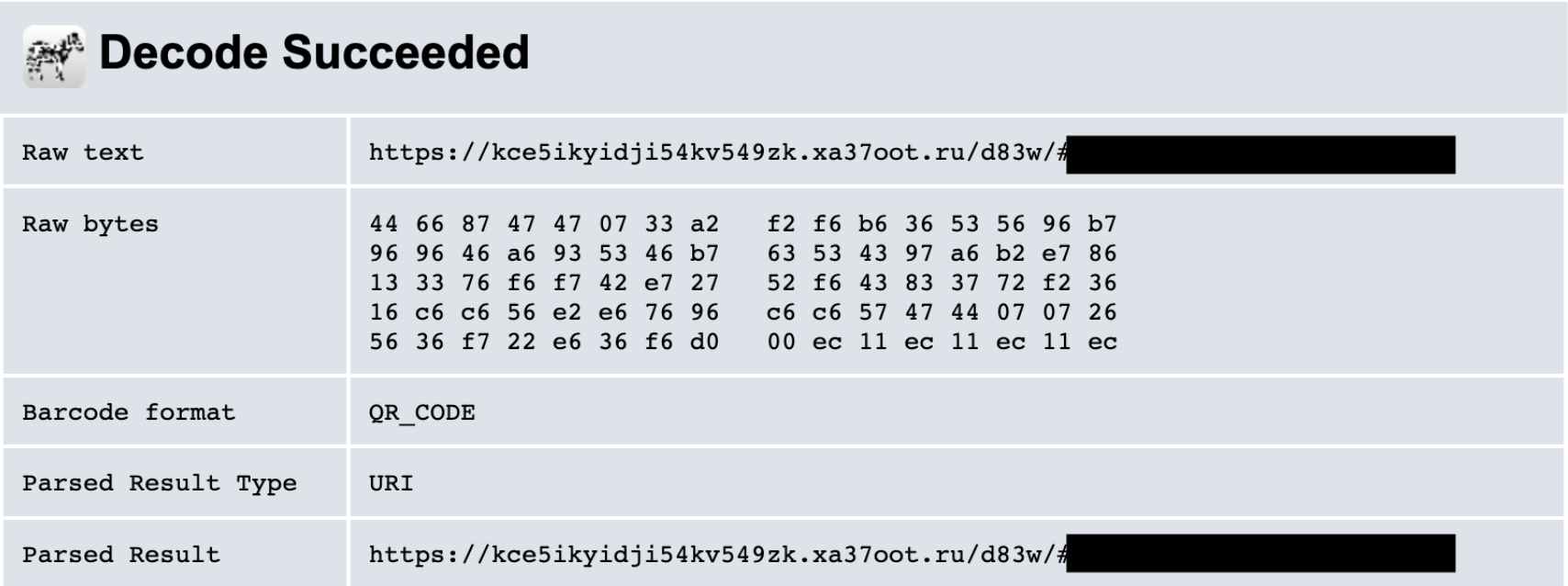

As mentioned in previous blogs, our analysts break down email submissions or vendor alerts to analyze the qishing attempts. Below are the steps we take to triage:

- We upload the QR code to a third party decoder tool called ZXing. (Information blacked out to avoid releasing customer information.)

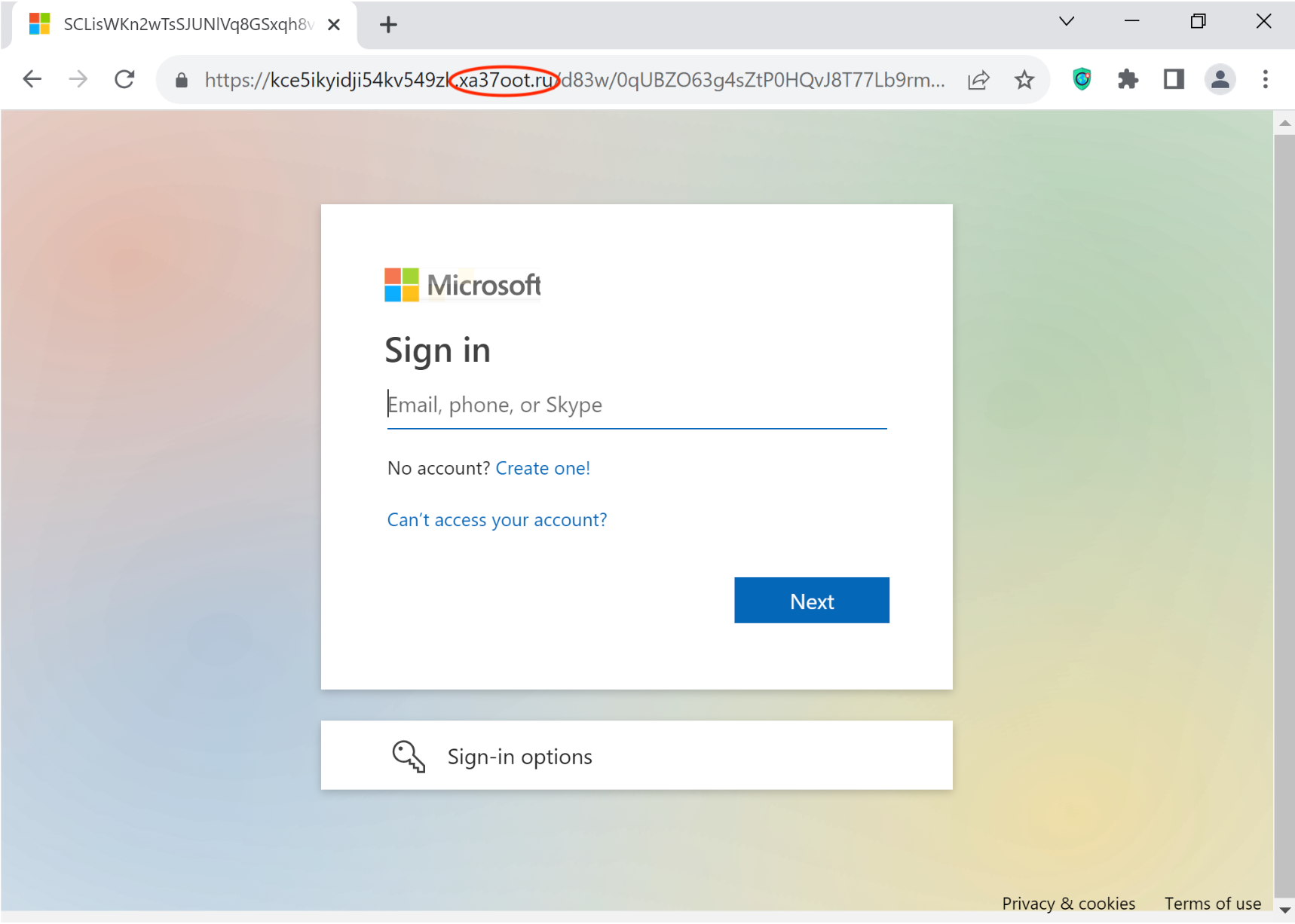

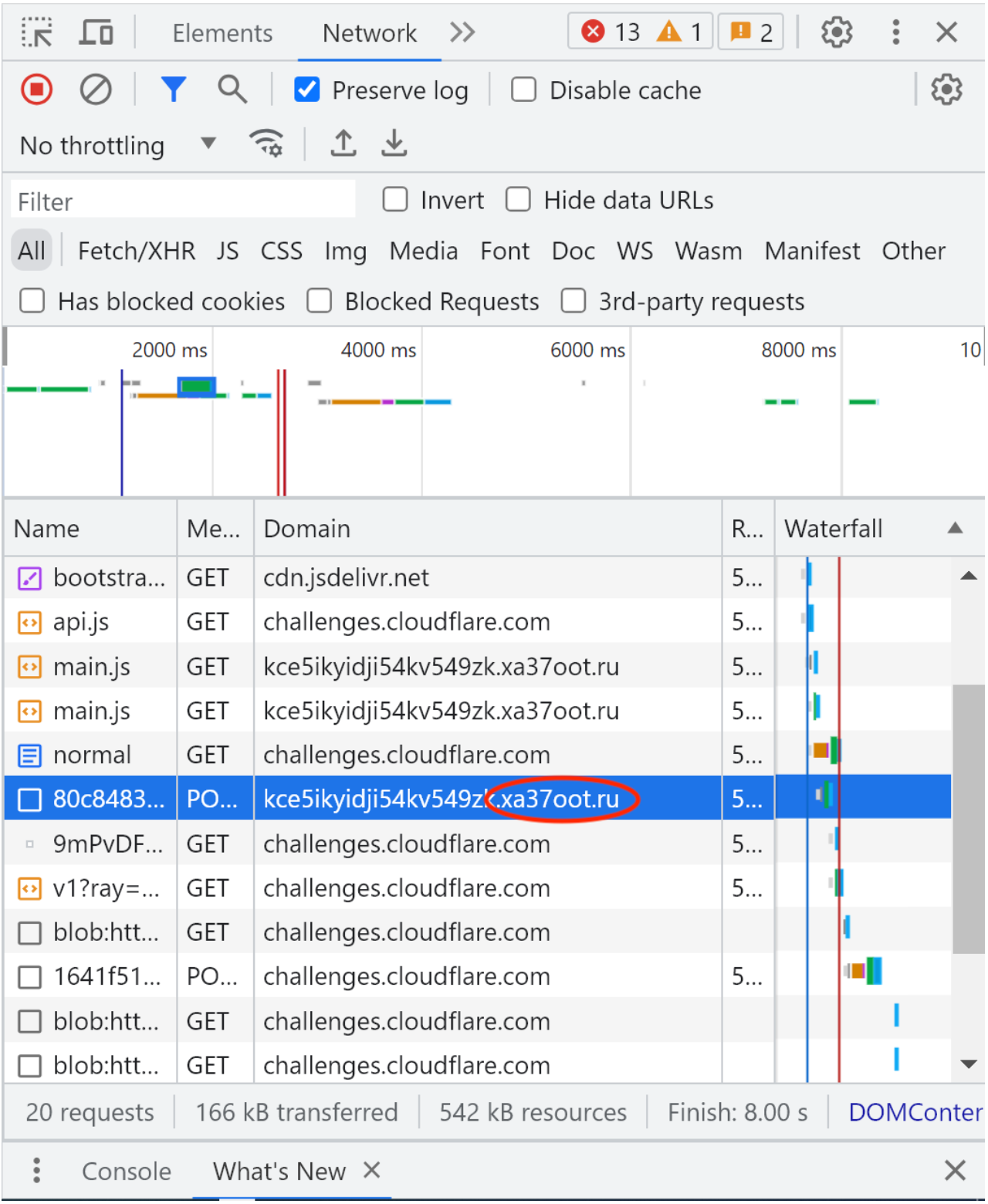

- After we have the encoded URL, we use a virtual machine or sandbox to analyze the destination. For example, let’s say the landing page is a fake Microsoft sign-in portal under the domain xa37oot.ru. We use dummy credentials to determine where the actual credentials are sent. Here, it’s the same domain as the landing page.

After identifying the malicious domain(s), we use our security operations platform, Expel Workbench™, to search for any suspicious network activity across our customer’s environment. Typically, our analysts also conduct endpoint scoping. However, users need to scan the QR code with their personal devices, and most organizations don’t cover security monitoring for end user personal devices. Instead we focus on a broad search within the customer’s environment and then run a more detailed search if there’s an evident threat.

To ensure a proactive approach to qishing, we elevate these attacks to a higher priority in the alert queue. We’ve created a YARA rule that identifies PNG files which are designated as “grayscale” in color. (A large majority of the reported alerts had attachments that fit this description.) While this doesn’t encompass all qishing attacks we receive, we’re actively researching the files and metadata of other codes to find other common indicators.

One of the biggest threats in qishing attacks is obviously that a hacker will wind up with internal credentials. However, the added threat in these attacks is that QR codes typically work through personal devices. If one of our customers scans these codes with a device we don’t have endpoint detection access to, neither the customer nor our security operations center (SOC) will be aware of the compromise. There’s a further threat: personal devices typically lack the same amount of protection as endpoint devices, meaning the usual security barriers in place could be bypassed more easily.