Security operations · 5 MIN READ · JEN BIELSKI · APR 9, 2018 · TAGS: Mission / Overview / Threat hunting

Sometimes the security landscape seems like a big game of telephone. A buzzword pops up. It may even be a good one. But then it enters the vendor echo chamber. Everyone starts repeating it to each other. The vendors CEO says “We’ve got to put that on our website.” The sales VP says “We’ve got to put that on our tradeshow booth.” And before long everyone in infosec is sayin’ it but nobody really knows what it means. Usually it’s defined as whatever the definer is doing. It’s kinda funny. But it’s really not. Because if you’re charged with making your organization more secure you’re left wondering what’s real(ly important) and whether you should care.

The term “hunting” is a good example. It has been kicking around for almost seven years since it was first introduced in 2011. The fact that it’s had more time to marinate than some of the newer buzzwords may be why it’s so confusing. Whatever the reason, at Expel we want to demystify what hunting is and what it’s not. So here goes nothin’.

What is hunting?

In short, hunting is a proactive effort that applies a hypothesis to discover suspicious activity that may have slipped by your security devices.

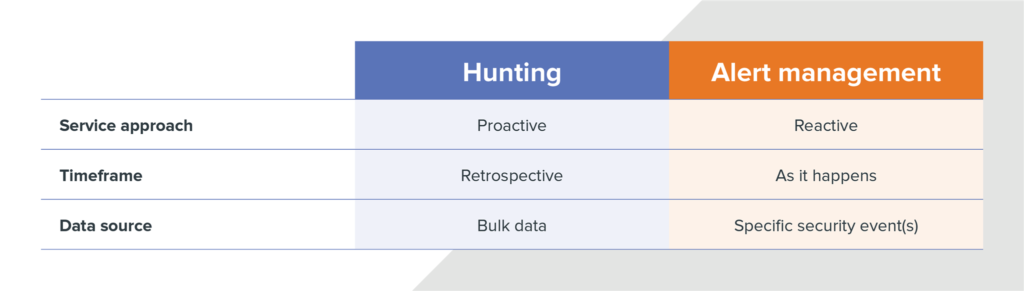

Now, that doesn’t mean you can’t use your security tools to go hunting (we’ll get to that in a bit). But looking at alerts coming from your endpoint detection and response (EDR) tool isn’t hunting. It’s alert management. And pretty much anything on this list also isn’t hunting.

Comparison of hunting vs. alert management

Here’s another way to think about it. With hunting you’re assuming that something has already failed and you’ve been compromised. The attacker has gotten past the perimeter (aka inside the network) and you’re looking for them. Since you don’t know where the attacker is hiding or who they’re trying to impersonate you’ll need to start with a theory based on common tactics attackers use. Then, once you know how you plan to seek out the attacker you’ll need to look to take a closer look to identify activity that looks a little off. Things that don’t look normal become investigative leads for an analyst to further review.

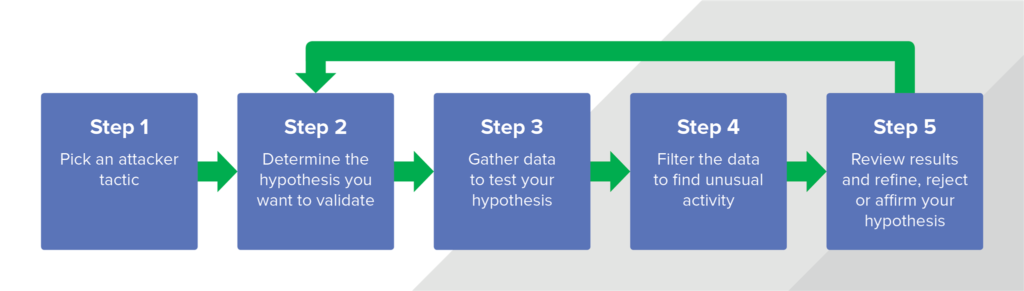

Hunting process overview

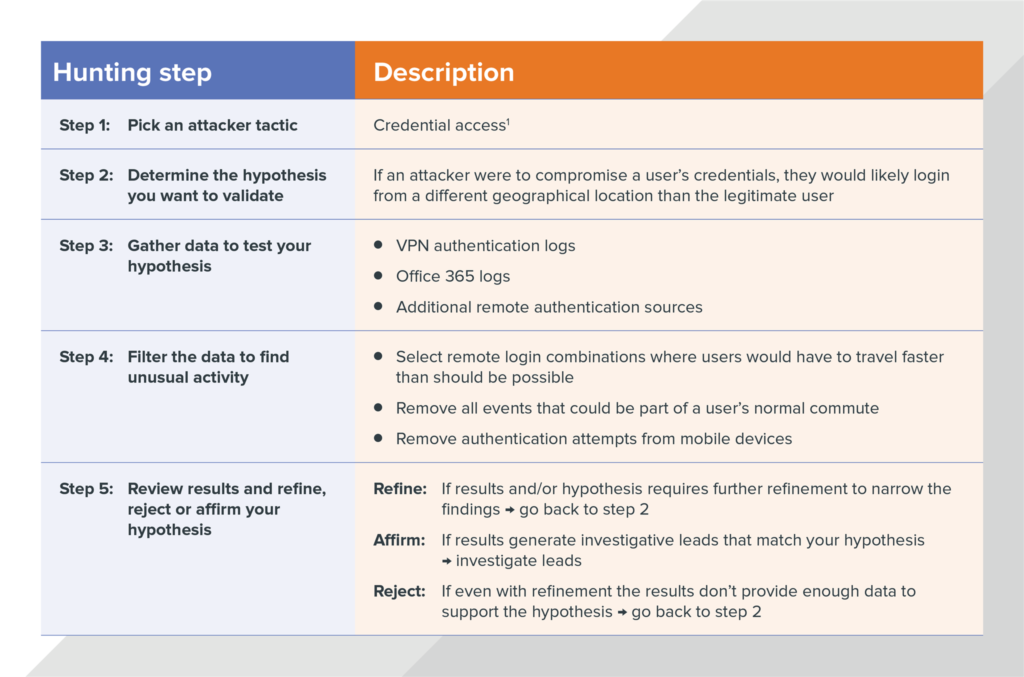

Example: Finding stolen user credentials (aka “You can’t travel that fast!”)

Attackers use lots of different methods to steal user credentials so they can blend in with normal activity and avoid suspicion. But when attackers use those stolen credentials to access a system their location is usually drastically different from the user’s real location. For example, an attacker in New York could login with stolen credentials and … thirty minutes later the real user could login in Los Angeles. Planes just don’t fly that fast (not to mention TSA). By reviewing the location of successful user logins, you can identify login activity that is too geographically disparate to represent legitimate user travel.

Here’s what that would look like if we applied the process we outlined above.

Hunting technique example: finding compromised accounts using login geo-infeasibility

What do you need to start hunting (the basics)

Now that we’ve talked about what hunting is, let’s identify the basic tools you’ll need to hunt. Here’s your shopping list starting from the hardest to find, to the easiest.

1. Someone (or some people) to do the hunting: That’s right. Hunting requires humans. Or at least human judgment to evaluate the data you collect. If you’re lucky, you may already have someone to perform this task. But if you’re smaller, or your security program is still maturing you’ll have to go hunting (heh) for someone. And that can be tough. Good threat hunters have typically done a stint on an incident response team, they’re itching to do some forensics and they’ve probably reversed at least one piece of malware just for fun. To translate, they’re not cheap, or easy to find. And once you find them you need to keep them (which can be easier said than done). Of course, if you decide you don’t want to or can’t find your own hunters, there’s a line of security vendors and managed detection and response (MDR) providers that would love to help you.

2. Security device to collect data: Once you’ve sorted out the pesky people problem, your next task will be to feed them some data. For that, you’ll need security devices. Endpoint detection and response (EDR) tools are a good place to start, but they’re not the be-all-end-all. Endpoints are a source of the truth, but your firewalls, SIEM or network forensics tool also collect data with crucial details for identifying malicious activity and filling out the story. The more data you can collect, the more you can hunt for. But don’t get hung up on the tools. At a minimum, if you’ve got either an endpoint or a network tool you’ve got what you need to get started.

3. A list of things to hunt for: Finally, you’ll need to decide what you want to hunt for. Knowing the tactic you want to sleuth out will guide the data you’ll need to collect and what outliers to look for.

The MITRE ATT&CK framework is a good starting point. In fact, it’s what we use here at Expel. It outlines the tactics and techniques attackers commonly use at each stage of the attack lifecycle. As you consider what you want to hunt for you’ll have to make sure that you have tools that can feed you the specific type of data you need. And be realistic about how much time you have.

If you choose to outsource your hunting capability, make sure you ask your service provider to explain how they’ll be hunting and how their techniques align with the security tools you’ve got. If their answers are squishy, it’s time to move on.

Is hunting right for your organization?

Now that we’ve (hopefully) taken some of the mystery out of hunting you may be wondering if it’s something that should even be on your radar. While it does provide an extra level of security, it’s not practical for every organization to implement a hunting program.

We recommend evaluating your risks and resources to determine if you should develop a hunting program. If you operate in a high-risk (and highly targeted) environment – think banks, defense contractors and companies that store large amounts of personal and financial information – then hunting probably makes sense because there are lots of adversaries trying to infiltrate your network.

But if your organization’s risk profile is medium- to low-risk, you’re likely the target of commodity malware and should evaluate where your resources are most needed. In that case, hunting can take up a lot of time and distract you from things that should probably be much higher on the priority list like effective anti-phishing controls, asset management, third-party assessments and a myriad of other things that make up an effective cyber risk program. Doing security right is difficult, and focusing on hunting when you should be focusing on building a more secure foundation can actually make you less secure.

Either way, you should make a conscious decision about whether you’re hunting or not. Don’t accidentally start hunting because your staff started chasing shiny things and found themselves looking at suspicious activity all over your network.

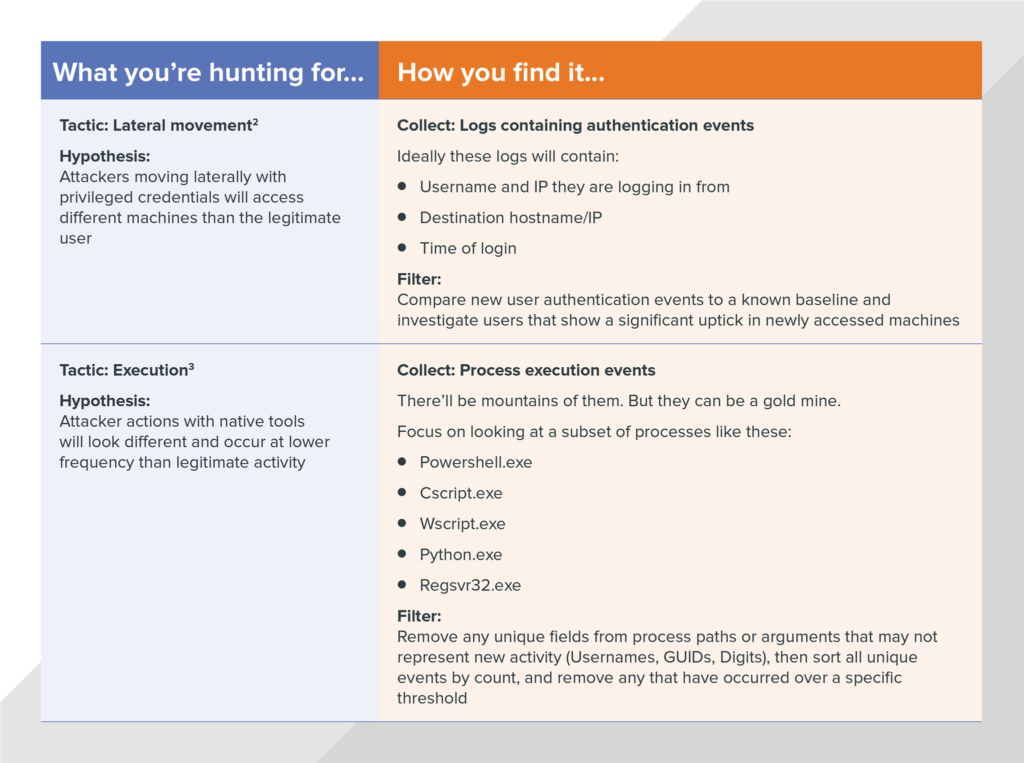

That said, if you decide a formal hunting program makes sense here are two good places to start.

1 “Credential access”. MITRE tactic description, https://attack.mitre.org/wiki/Credential_Access

2 “Lateral movement”. MITRE tactic description, https://attack.mitre.org/wiki/Lateral_Movement

3 “Execution”. MITRE tactic description, https://attack.mitre.org/wiki/Execution