Threat intel · 4 MIN READ · BEN NAHORNEY AND JENNIFER MAYNARD · APR 10, 2025 · TAGS: Vulnerability management

TL;DR

- Atlas Lion is a cybercrime group based out of Morocco that targets organizations issuing gift cards.

- We’ve observed the group using stolen credentials to enroll attacker-controlled VMs into an organization’s domain.

- The incident highlights the importance of having automated device enrollment processes in place to set up new devices securely.

We’ve recently observed an unusual attack technique that, while discussed in cybersecurity circles, we haven’t previously seen put into practice in the wild. This technique could go unnoticed under the right circumstances, allowing an attacker to stay undetected for longer, simply by hiding in plain sight. This is done by using stolen credentials to enroll new systems they control—mimicking normal workstations and servers within the targeted network’s infrastructure.

The threat actor behind the attack appears to be Atlas Lion, based on indicators of compromise (IOCs) our SOC observed during the incident. Atlas Lion is a cybercrime group based out of Morocco targeting organizations that issue gift cards—big-box retailers, apparel companies, restaurants, etc. The group’s primary goal appears to be redeeming or reselling the stolen gift cards they obtain during their attack campaigns.

Atlas Lion is also known for having an extensive understanding of the cloud, often leveraging such infrastructure in their attacks. The group uses this knowledge to carry out reconnaissance, often reviewing internal documentation to learn more about the processes involved in gift card issuance. The group is also known to utilize free cloud service trials to set up their attack infrastructure, which also allows them to easily dispose of it when the trial expires or it’s identified as malicious.

In like an Atlas Lion…

The attack began with an SMS phishing campaign. Based on public information about this stage of the attack, Atlas Lion’s SMS messages often appear as though they come from internal resources, such as a notification that a helpdesk ticket has been opened for the user. These messages include a malicious link designed to look similar to the target organization’s domain.

If the recipient clicks the link, they are brought to a phishing site designed to mimic the look and feel of the organization’s legitimate pages. If they input their credentials—username, password, and MFA code—the attackers automatically send the credentials to the company’s official login page behind the scenes. A session cookie is generated by the legitimate service and sent to the attackers as they log in, allowing them to bypass MFA requirements as they move the attack forward.

New device, who this?

The fact that the attacker managed to successfully log into an MFA-protected account is concerning. But those sessions will eventually expire, logging the attackers out of these compromised accounts.

To prepare for this eventuality, Atlas Lion faced the challenge of not having another MFA code or session cookie to maintain access. Without either, they faced a limited window during which they could carry out their attack, or had to come up with another approach.

So if MFA is required, why not enroll a new MFA device under the attacker’s control?

This is exactly what the attackers did. Since they had access to a user’s account, they simply enrolled an MFA authentication app of their own. Then to shore up their control of the account, they changed the user’s password.

They were now poised to attempt a bolder strategy of device enrollment.

A lion in sheep’s clothing

Once an attacker gains initial access to a system in a network, frequently, the next step is to elevate privileges and gain persistence on that system. The risk attackers face in these cases is this activity often deviates from normal, day-to-day activity. And if these systems are monitored, it makes it easy to detect, investigate, and mitigate the malicious activity.

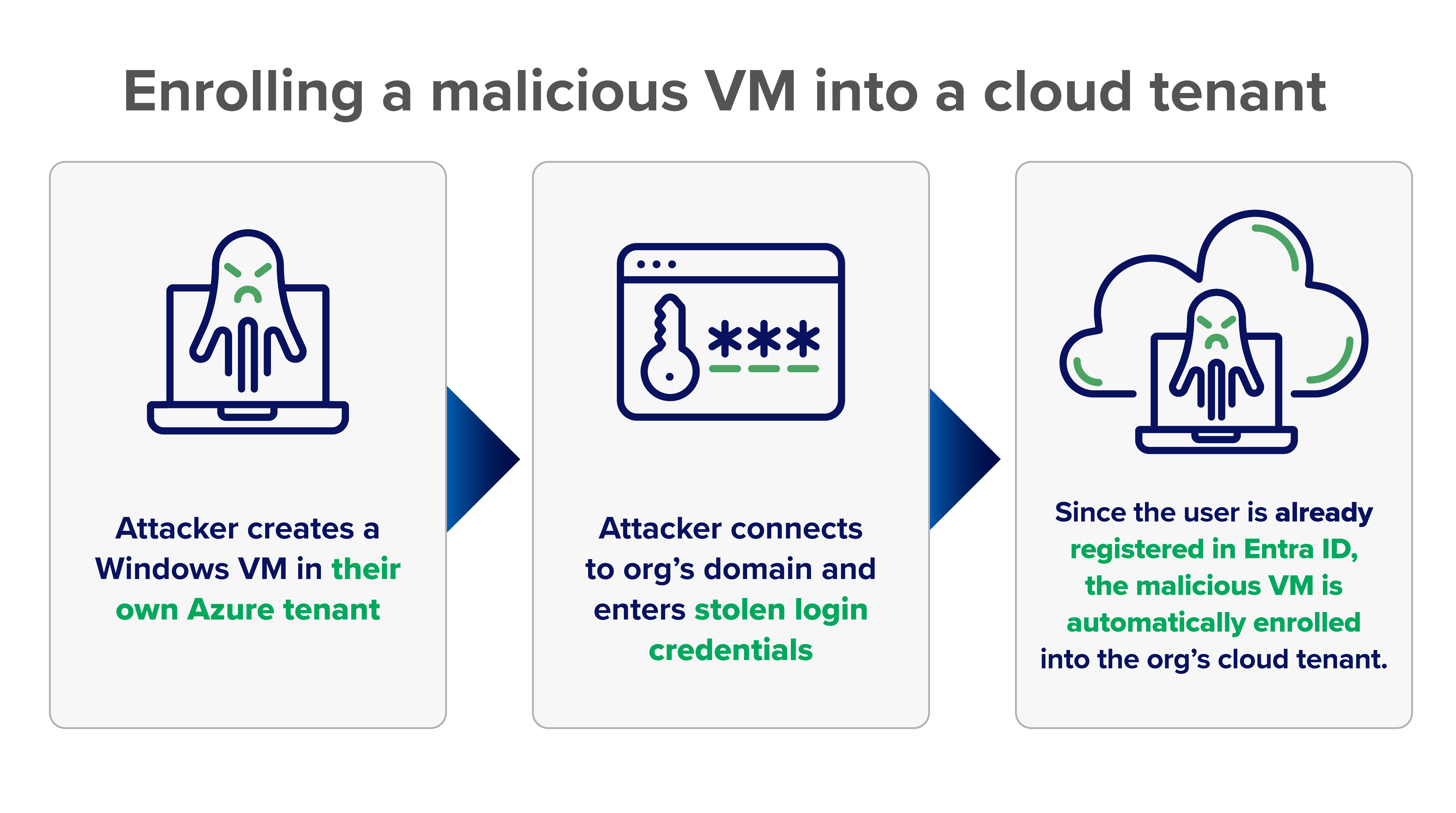

Atlas Lion didn’t take this well-trodden path. Instead, they started by creating a Windows virtual machine (VM) in their own Microsoft Azure cloud tenant. Since the compromised user was already registered in Entra ID, the attackers simply entered the stolen credentials they had obtained and, when prompted, the MFA code from the newly registered authentication application.

This successfully validated the user, and the attacker’s VM was connected to the organization’s domain and enrolled. This happens as part of the normal Windows device setup, as it offers to join the device to a corporate domain if an account is provided.

This effectively took a VM mimicking a brand new system within the corporate environment and onboarded it as a new system, bypassing requirements put in place to keep unauthorized devices off of the corporate network.

…out like an atlas lamb

The fact that an attacker was able to leverage an organization’s cloud infrastructure to enroll a system they control is concerning, but fortunately the same brazen attempt is what led to its downfall.

While enrolling a new system into the network, the target organization required several software applications to be installed for the new device to meet compliance requirements. One of these applications was Microsoft Defender. So as the attacker’s device was enrolled into the organization, the endpoint security software was installed on the attacker’s VM. And Defender recognized something wasn’t right.

Interestingly, it wasn’t the actual activity that brought attention to this attack. It turned out the bad actor was using a previously flagged IP address with a history of malicious activity.

This IOC immediately led to an alert in the Expel queue, which a SOC agent picked up shortly thereafter. Fifteen minutes later, the analyst suggested kicking the host off the network, along with other remediation steps to expel the malicious actor, such as resetting the users credentials.

An event worth taking note of

It’s mildly ironic that the enrollment of a malicious, attacker-controlled system was brought down by the same enrollment process the attackers were attempting to take advantage of.

But what’s more concerning is that it could be argued that the attackers were careless. If they had simply used an IP address that wasn’t known for malicious activity, it’s difficult to say if the malicious device enrollment would have been noticed as quickly.

This highlights the importance of having automated device enrollment processes in place to set up new devices securely. In this case, it was the endpoint security tools installation after device authentication that stopped the attack.

It’s also important to have network access control policies in place that require specific configurations to connect to the environment. This would include ensuring the user is connecting from a geographic location and an IP address space matching where they reside.

There should also be policies in place to prevent the arbitrary enrollment of devices without prior authorization. It’s rare that an employee will need to authenticate new devices, so putting guardrails on this process will also help block these types of attacks.

Is this the end?

It’s important to note that while this may appear to be a happy ending, Atlas Lion did not just throw up their hands and give up on attacking this organization. With Expel’s help, the organization won the battle, but the war was far from over. More to come in part two.