Current events · 4 MIN READ · BRIAN BADORREK · AUG 31, 2023 · TAGS: Guidance / Phishing

Adversary-in-the-middle attacks (AiTM attacks) are effective at bypassing MFA and conditional access defenses. Here are some tips to help safeguard your organization.

You may think multi-factor authentication (MFA) and conditional access will protect your users from compromise, but we’ve seen time and time again that MFA alone isn’t a silver bullet. While MFA and conditional access prevent a lot of unauthorized logins, attackers can bypass location-based conditional access controls via a virtual private network (VPN) service, allowing them to appear as though they’re in the same city as your end users even though they could be on the other side of the world.

One of the most common ways we see attackers defeat MFA is through an adversary-in-the-middle (AiTM) credential harvester‚ a modern tactic that includes a prompt to capture an MFA code and authenticate in real time. This is a frequent infection vector leading to BEC, and was a common tactic recognized in our just-published Quarterly Threat Report (QTR) for Q2 2023.

Common BEC incident timeline

Here’s what a typical business email compromise (BEC) attack could look like:

- Attacker logs in using MFA from an AiTM server

- Attacker then logs in with a session token from the AiTM server

- Attacker registers a new MFA device for persistence

- Attacker deletes the original phishing email

- Attacker performs mailbox reconnaissance

- Attacker creates a malicious inbox rule to conceal activity from the end user

Let’s dive a bit deeper to better understand each of these steps and what their detections should look like.

1. Attacker logs in using MFA from an AiTM server

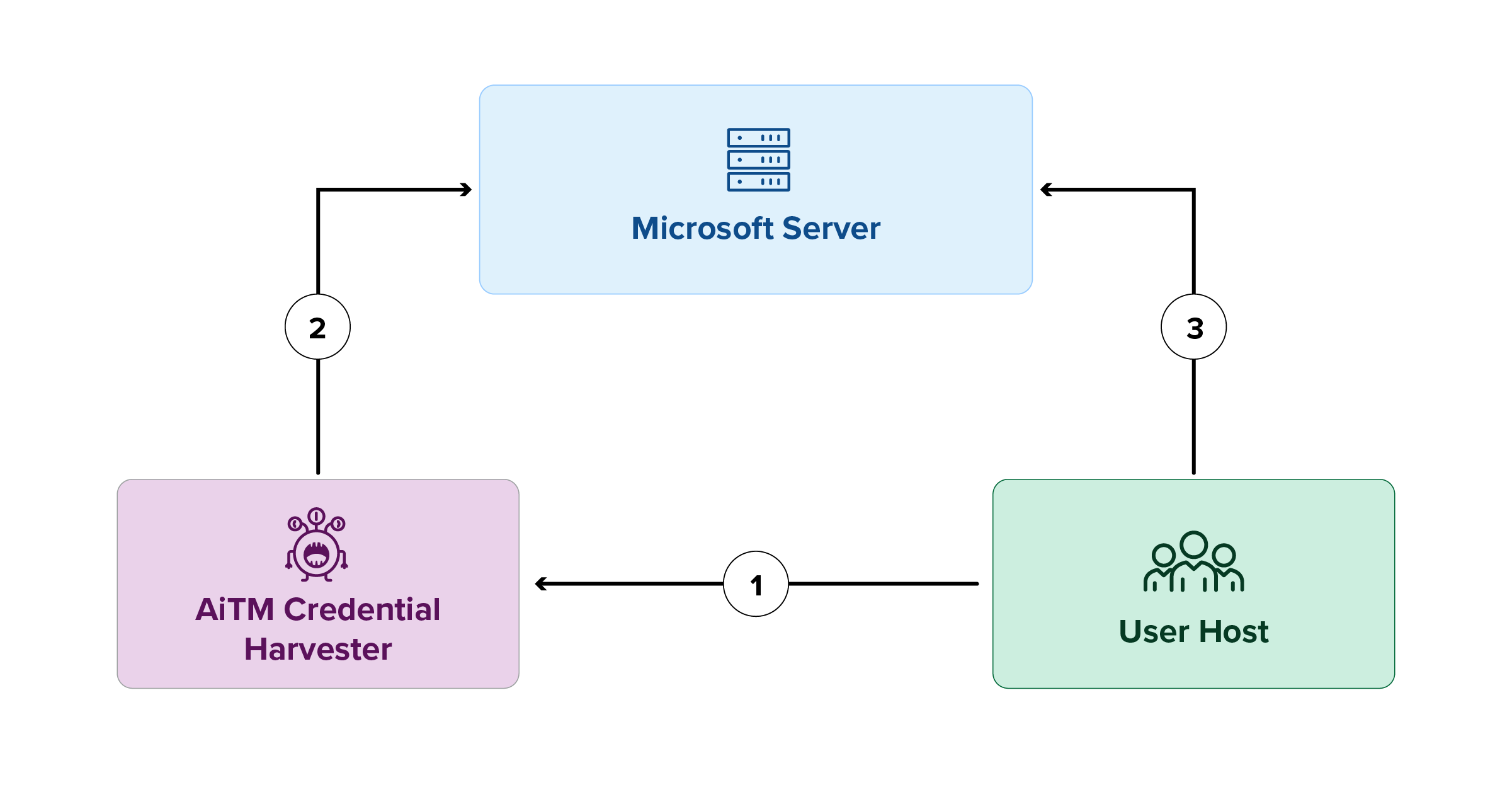

AiTM attacks often use credential harvesters are phishing pages that mimic both the look and functionality of a legitimate login portal. They sit between the user and the legitimate portal, capturing user input and passing it along to the legitimate login portal in real time. We often see them impersonating Microsoft 365 (M365) login portals, positioned between the user and Microsoft server.

Figure 1

By passing the user’s credentials and MFA code to the Microsoft server, the AiTM server authenticates itself into the user’s account.

After successful authentication, the AiTM server redirects users to the legitimate login portal, where they’re given the option to authenticate.

Figure 1 shows the steps in this process.

- Step 1: User enters credentials on the phishing page

- Step 2: AiTM server relays credentials to the Microsoft server and authenticates

- Step 3: User is redirected to the Microsoft portal

Detection: this attack is best detected using more traditional anomaly-based detections as well as looking for geo-infeasible logins.

However, an additional AiTM login detection method takes advantage of step 3. In the unified audit logs (UAL), steps 2 and 3 are recorded as consecutive logins from different IPs which occur within about 30 seconds of each other—and often within only a couple of seconds. The first login will be the AiTM server (step 2), with the second login being from the user’s legitimate IP address (step 3).

Detection: look for consecutive login events to an account from different IP addresses occurring within 30 seconds of each other, both with MFA satisfied.

Depending on your environment, you may need to tune out some noisy IPs. However, after tuning, we’ve found this to be a low-noise/high-fidelity detection.

2. Attacker then logs in with the session token from the AiTM server

The login from the AiTM server is just a script programmed to pass along the credentials and create a new login session.

A human attacker will use this token to authenticate at a later time. From our observations, the subsequent login from the attacker often comes from a different IP address.

Detection: the subsequent login is best detected using traditional methods, such as anomaly-based detections, geo-infeasibility, and looking for properties outside of the user’s baseline.

3. Attacker registers a new MFA device for persistence

Once authenticated, attackers will register their own MFA devices as a form of persistence. Why? Their session token won’t be valid forever. Registering their own devices gives them a way to bypass MFA in the future if needed.

Detection: look for the “User registered security info” event to detect when a user registers a new MFA method.

4. Attacker deletes the original phishing email

Attackers often cover their tracks by deleting the phishing email that led to the credential harvester. This event, recorded as MoveToDeletedItems, simply moves an email to the Deleted Items folder. It’s followed by a SoftDelete to mark the message as deleted and/or HardDelete, permanently deleting the email.

5. Attacker performs reconnaissance in the mailbox, particularly in the Sent Items folder

Before creating an inbox rule, the attacker will scope around the inbox looking for emails of interest. Often the goal is to hijack an existing email chain. A good place to look for these are in the Sent Items folder. While the UAL doesn’t log every individual email accessed (MailItemsAccessed does that), it does log when an attachment is opened (under the “Update” operation with the “modified properties” field set to “AttachmentCollection”). It’s common to see several of these events as attackers are performing recon on the mailbox.

While both of these steps—deleting emails and inbox recon—probably don’t need detections themselves (because of noise), they’re good tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) to keep in mind while investigating a potential account compromise.

6. Attacker creates a malicious inbox rule to conceal this activity from the end user

Attackers create inbox rules to move incoming mail matching certain parameters to another folder (to hide them from legitimate users, who may also be active in their mailbox). The rules are usually configured to move emails to the Deleted Items, Archive, and RSS Feeds folders.

Detection: alert on inbox rule creation (New-InboxRule, Set-InboxRule) with parameters, move to the following folders: Deleted Items, Archive, and RSS Feeds.

AiTM attacks are sneaky and dangerous, but informed security operations center analysts can do a great deal to short-circuit them before they have a chance to cause damage. For more information on some of the attacks we’ve seen recently, check out our QTR. If you have questions or comments, drop us a line.