Rapid response · 5 MIN READ · MYLES SATTERFIELD, TYLER WOOD, TEAUNA THOMPSON, TYLER COLLINS, IAN COOPER AND NATHAN SORREL · JAN 6, 2023 · TAGS: AWS / tech stack / threat landscape

What happens when attackers get their hands on a set of Amazon Web Services (AWS) access keys? Well, let’s talk about it. In this post, we’ll share how that scenario led to our security operations center (SOC), threat hunting, and detection engineering teams all working together on an incident.

We love it when incidents teach us new things, helping strengthen our service delivery and keep our customer environments safe.

We’ll walk through the entire incident step-by-step to highlight not only what caught our attention, but how we capitalized on a situation that our customers don’t often see.

Initial lead and detection

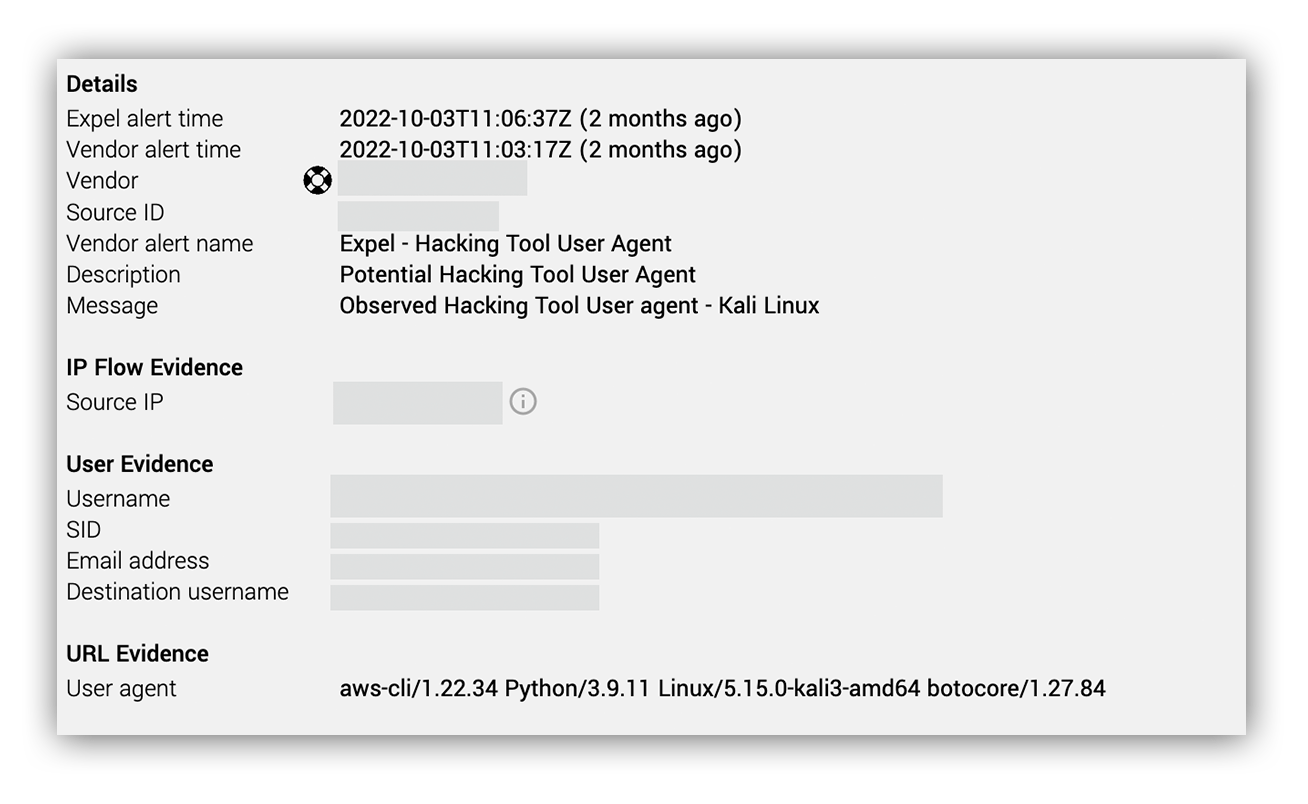

The initial alert lead indicated authentication with a suspicious user agent. The alert messageーObserved Hacking Tool User agent – Kali Linuxーsuggested that the user employed the Kali Linux operating system. Weird.

A closer look at the user agent in question revealed that it was more specifically aws-cli/1.22.34 Python/3.9.11 Linux/5.15.0-kali3-amd64 botocore/1.27.84.

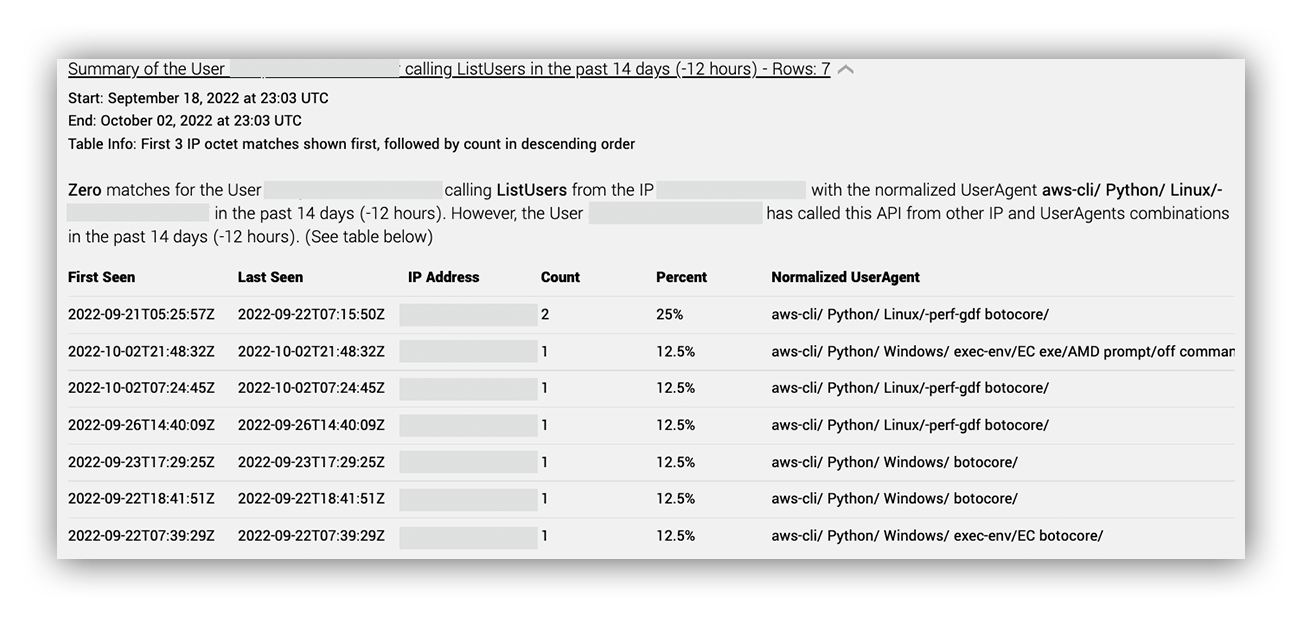

Based on the contextual enrichment below, this AWS user account had not previously used a Kali Linux useragent within the previous two weeks.

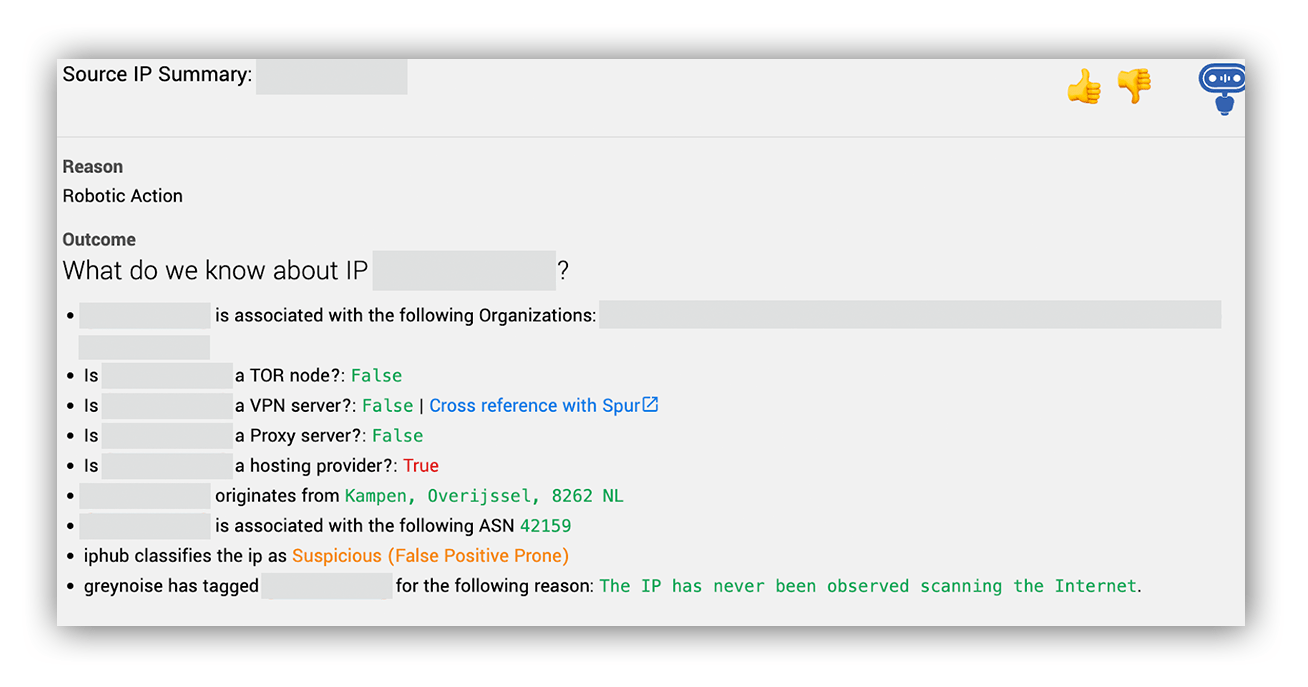

But what about the IP address associated with this activity? Ruxie™—our friendly bot responsible for triage—automatically pulled some information for us. We then saw that the IP was allocated to a hosting provider other than AWS, Google, or Microsoft, and also that it wasn’t located in a typical area for this customer.

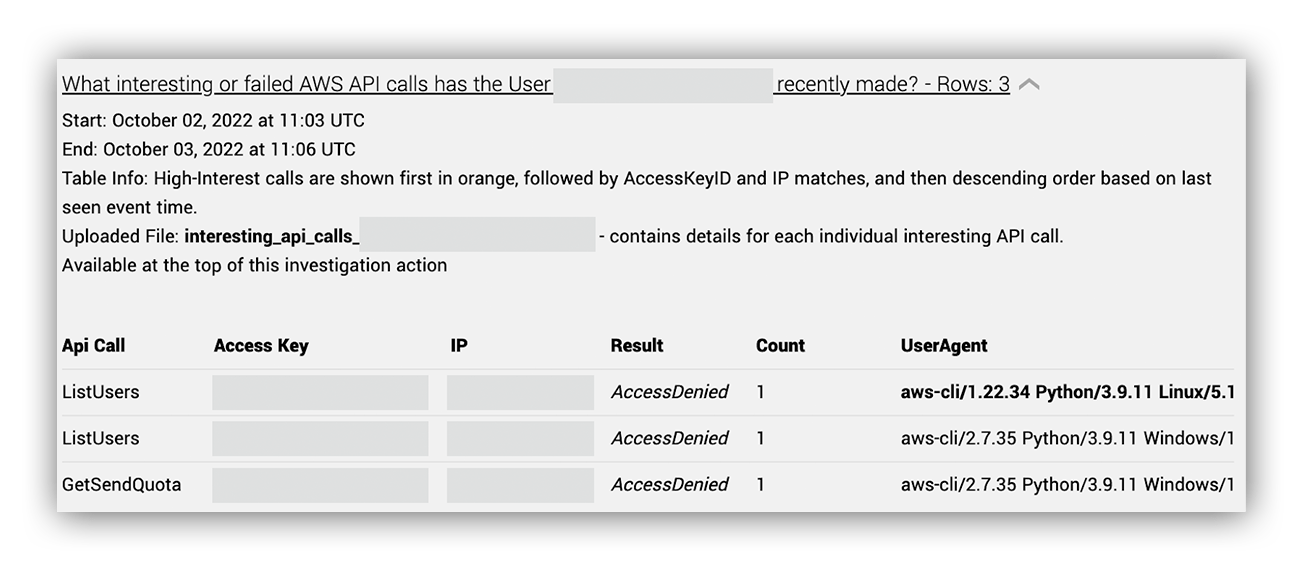

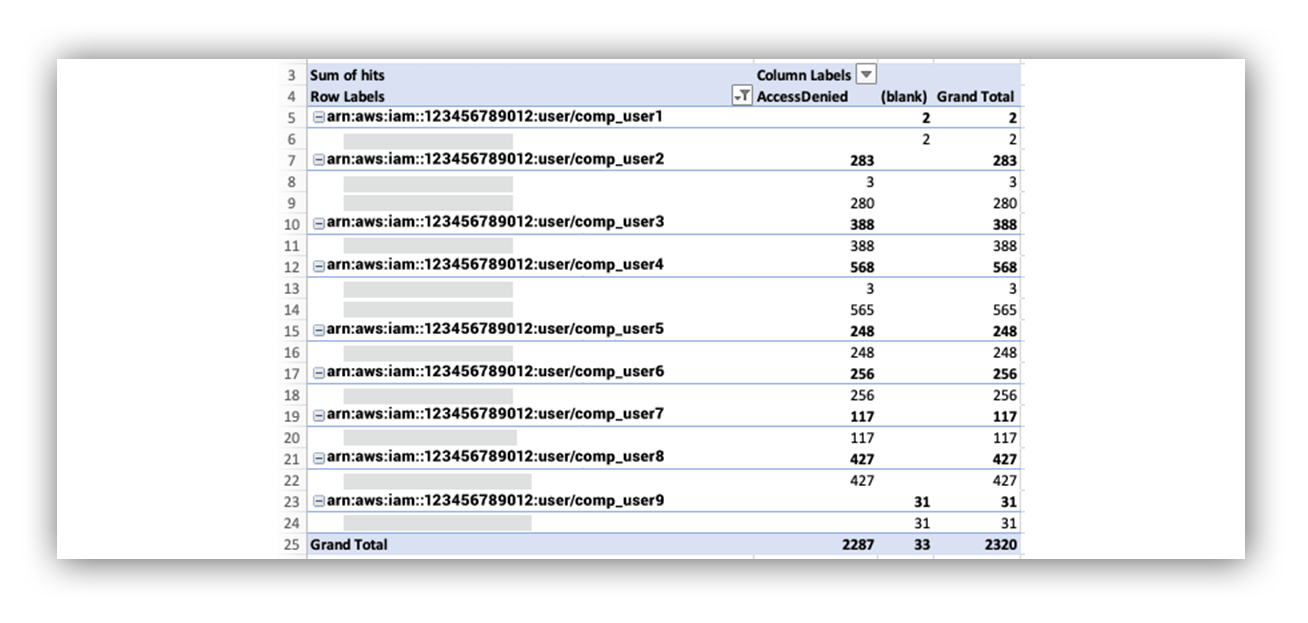

At this point, we’re ready to call this an incident and let the customer know that we had something interesting on our hands. We issued remediation actions to reset credentials for the user and disable the long-term access key. Once we classified it as an incident, our next step was to see everything that the user, IP, and access key did, so we ran an AWS triage on all of them. Let’s take a closer look at what Ruxie told us the user was doing. Using our AWS user enrichment workflow, we can quickly identify which IPs the user usually performs activity with and any interesting or failed AWS API calls. Here we saw three API calls: (two) list users, and one GetSendQuota (our threat hunting team will tell us why this is important). All were denied and all came from the same access key, but different user agents. Interesting.

Using our leads, we scoped additional activity in the compromised environment. As noted earlier, this led to the discovery of additional AWS IAM accounts/access keys. Seven to be exact. We repeated our remediation actions for those accounts/keys.

Too long; didn’t read (TL;DR)

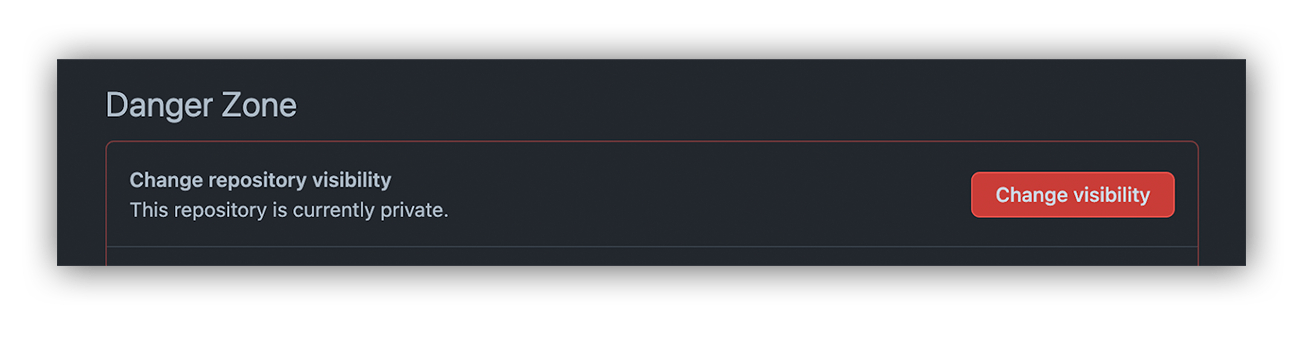

The attacker gained access to the customer environment through the use of stolen long-term access keys. Scoping surrounding activity for the AWS account, we saw that the attacker was attempting to use seven different access keys and accounts. How were the AWS keys compromised? During the initial triage, we didn’t find evidence of any exploited services. We turned to open-source intelligence gathering and performed some simple Google searches to see if there were any obvious candidates for exposure. Using patterns observed in the affected IAM account names, we came across a publicly exposed Postman server with access key credentials stored in the project’s variables.

Threat hunting

While examining what was known about the newly created incident, we noticed an event type we didn’t recognize: GetSendQuota. It’s not one an attacker typically uses, and anomalies are interesting to hunters, so we began running queries and doing some research.

- What does ‘GetSendQuota’ do?

- Who else is running that event type?

- Does this organization use this event commonly?

- Did anything else stick out as atypical?

Some Googling revealed that GetSendQuota was an Amazon email service feature that “provides the sending limits for the Amazon SES account.” In scoping the customer’s historical activity, we saw that this event was called very rarely and only by a confined set of users. One of them we could eliminate easily, as it was a service account running automated tasks. The remaining users were interesting, and I noticed several error messages all interacting with the same account.

Taking the access_key_id for the initial lead, we looked up what else it did. Most of that user’s activity was Amazon SES-related (around 95%) and we were able to find other events that stuck out as unusual. “UpdateAccountSendingEnabled,” specifically, seemed interesting, as it was called several times (but not excessively, and it seemed to toggle a useful service on or off). Documentation indicated that it “enables or disables email sending across your entire Amazon SES account in the current AWS region.”

Isolating this event type in the whole environment confirmed that only six users ever employed this event type. All six overlapped with the group of users from the previous query.

This gave us high confidence that all six were compromised. Subsequent queries using the observed source IP addresses for the compromised accounts led us to one more owned account.

Interestingly, as we are always researching threat hunt methodologies, we ran a separate hunt against this customer’s data looking for common “groupings” of attacker events. That hunt didn’t suggest that these accounts were suspicious. It was a useful exercise because it showed that these attackers were consistent in their behavior. But they weren’t doing things the way other bad actors did.

For this attack, event prevalence and feature overlap were key to isolating all compromised accounts. This attacker’s focus on email infrastructure was noteworthy and has led us to compile some of these event types into a new “email event buckets” to hunt on in the future.

Detection opportunities for stolen access keys

This incident presented a unique scenario to detect against. Hopefully, all defenders in AWS are concerned about attackers stealing an access keyーespecially a long-term access key. This is what keeps us defenders up at night, and is the reason digital watering holes like GitHub have warnings about making resources available to the public.

The above is quite a standard scenario. However, when attackers gain access to multiple access keys, their behavior may change a little bit, giving blue teams another behavior to key on.

When an attacker scores some trust material like an access key, or lands on a box (gains access to a new device) which they’re unfamiliar with, they’re likely to perform some enumeration to figure out what powers they’ve gained. Enumeration of this type can be difficult to detect due to high volume events that are of little concern. Sometimes administrators and infrastructure tools like CloudFormation perform enumeration API calls multiple times a day.

In this incident, we noticed the attacker performing the same enumeration activity from the same sources, with multiple access keys. Hunting through our customers’ environments, we found that enumeration of multiple access keys is rare. Specifically, the attacker used the API GetCallerIdentity using multiple access keys and from the same IP. GetCallerIdentity is similar to the bash command whoami and gives the attacker information about where they have landed.

Since it rarely happens, is it even worth it to build a detection? Yes, absolutely, because stolen access keys are among the top vectors for initial access into an AWS environment.

Key Takeaways

- Remediation:

- Deactivate the access key associated with the IAM account

- Using an abundance of caution, reset the AWS console password associated with the IAM account (recommended)

- Block the source IP address (recommended)

- Detections:

- AWS Access Key Enumeration: multiple recon API calls (GetCallerIdentity) on multiple AWS access keys from the same source IP

- Threat hunting:

- Attackers commonly have their own playbook and will keep working it. We can use that to our advantage by looking for similar activity elsewhere (or being executed by different users). We can also use this knowledge to do threat hunting audits long after the original event has been remediated. If you missed some persistence mechanism that was originally established by the attacker, you will be able to see it later if you keep looking for that playbook of events.

- Common activity is our best friend. Any single environment will have patterns that line up with the daily activity of its admins and users. Attackers won’t know these patterns and will stand out. Knowing your organization’s patterns will help you see attackers.

- Research and humility are key. Not all attackers are the same. Not all of them will utilize “GetSendQuota.” It’s easy to get complacent and think you know what an attacker might do…only to observe an attack unlike any you had seen before.