MDR · 3 MIN READ · BRYAN GERALDO · SEP 27, 2023 · TAGS: Threat hunting

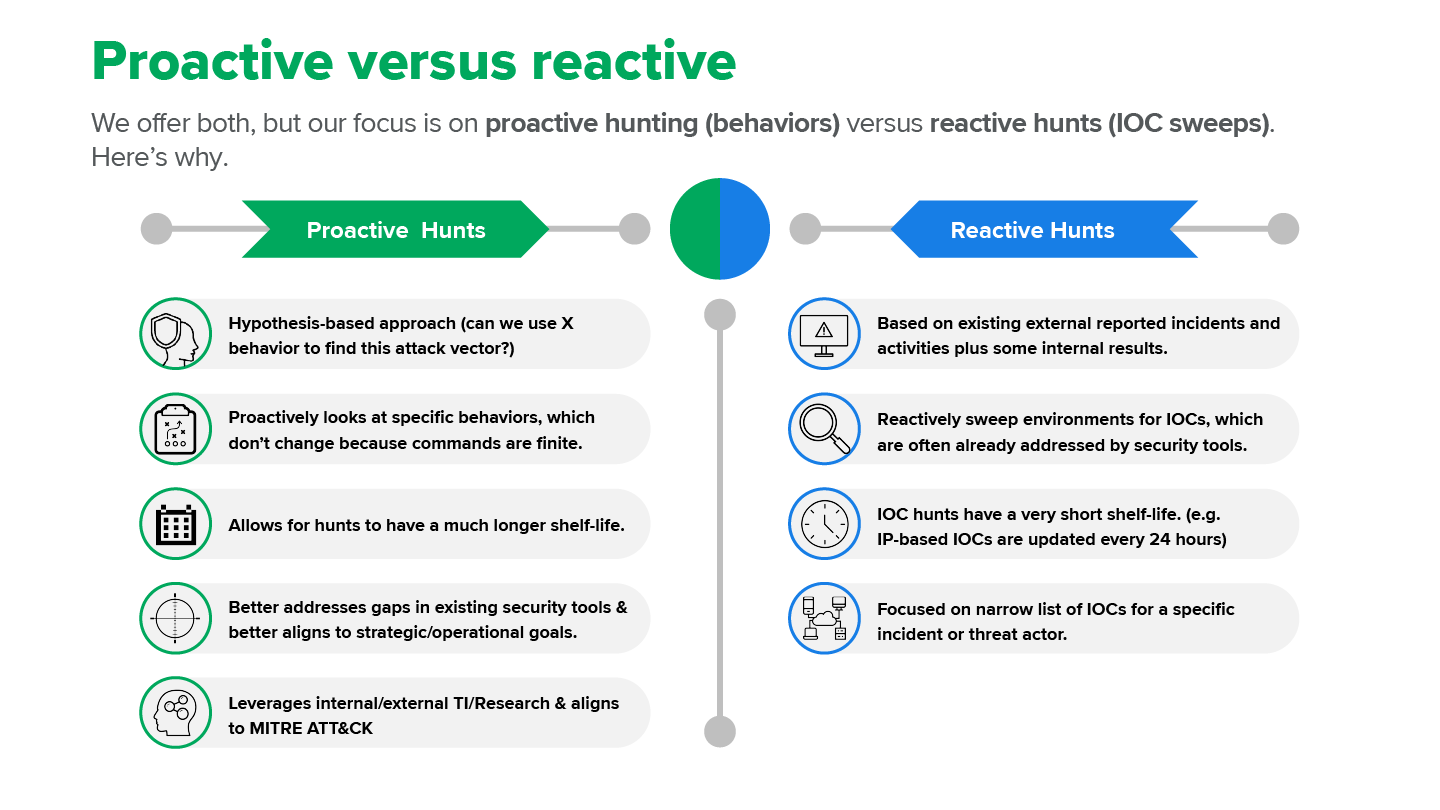

Threat hunting comes in two flavors: proactive and reactive. There are important differences, and here we explain what they are.

Some history on “threat hunting”

The first well-documented mention of threat hunting is in Richard Beijtlich’s (of Mandiant fame) oft-cited Information Security article from July–August 2011. In “Become a Hunter: Fend off modern computer attacks by turning your incident response team into counterthreat operations,” he writes:

To best counter targeted attacks, one must conduct counter-threat operations (CTOps). In other words, defenders must actively hunt intruders in their enterprise. These intruders can take the form of external threats who maintain persistence or internal threats who abuse their privileges. Rather than hoping defenses will repel invaders, or that breaches will be caught by passive alerting mechanisms, CTOps practitioners recognize that defeating intruders requires actively detecting and responding to them.

The other key idea informing the concept of threat hunting derives from the military term “hunter-killer,” which denotes a naval craft designed to locate and destroy enemy vessels. The term focuses on proactively hunting and eliminating a threat, which is why the concept is so well suited for cybersecurity.

Then, in his 2013 book, The Practice of Network Security Monitoring, Beijtlich breaks down threat hunting into two categories: Indicators of compromise (IOC)-centric analysis (aka matching) and IOC-free analysis (aka hunting).

Threat hunting today

So why, after all this time, do so many people hang onto the idea that hunting is about IOC matching/sweeps—what many call reactive hunts—from threat intelligence sources? Is it because many organizations use cyber threat intelligence (CTI) as a primary driver for hunting? Is it because so many CTI-focused security vendors use the term hunting too liberally? Or is it that no one has really done a good job of defining hunting? (I seriously doubt that last one, but I figured I’d throw it out for discussion.)

I suspect the first two reasons explain why so many in security see IOC matching/sweeps as <air quote>hunting</air quote>. I also think this speaks volumes about the misapplication of tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) within CTI, which is harder to apply and should be one of the main drivers—besides IR data/an understanding or your infrastructure/external threat bulletins—in informing your hunting program. (Someone should do a study on this. Not it…)

The cycle should work like this

- The CTI organization should have existing strategic and operational goals based on an understanding of the organization’s infrastructure and ongoing business requirements (e.g., the client is going to deploy Azure Virtual Desktop (AVD) as part of a migration for all new mergers).

- The CTI team has seen recent TTPs tied to specific attacks against AVD.

- The IR team provides information about blind spots in the existing infrastructure and the CTI team provides TTPs.

Using both of these pieces of information, the threat hunting team can then develop specific hypotheses for structured hunts. Here’s an example based on this use case:- Attackers are using compromised credentials to gain access to AVD. Can we detect users that are 1) bypassing identity security controls, 2) gaining a foothold in AVD, and 3) attempting to move laterally within AVD? (We know—this is an ambitious hypothesis, since it would likely involve two or three different hunt techniques.)

Note: Remember, TTPs are important because attackers are limited to the same sets of finite commands used by everyone in the industry. For this reason, TTPs tend to have longevity, whether the attacker is living off the land in an on-premise environment or cloud infrastructure.

Your organization’s threat hunting program should focus on looking for TTPs, holes, and areas of concern around your security posture and create hunts to probe those areas. Further, the results of these hunts (i.e. true-positive or false-positive) should be used as a feedback loop for CTI, IR, and Hunting to iterate security processes.

Don’t get me wrong. IOCs have their place. Specifically:

- They should be used/ingested by security tools to increase their capabilities to identify newly reported threats.

- They can also be used, on occasion, for an IOC sweep in the event that the security vendors have not added the latest IOCs. That said, most vendors (security products/CTI) do update IOCs regularly—usually within 24-48 hours.

- IOC scans are often used as a reactive measure by SOC teams when assessing impact from zero-day attacks, and while responding and remediating particular incidents within an organization. This is something many MDR providers, including Expel, offer as part of their service.

All that being said, in the world of threat hunting (hunter-killer), proactive hunting associated with TTPs should reign supreme. This was specifically called out in the recent report, The Forrester Wave™: Managed Detection and Response, Q2 2023.

Many MDR providers offer threat hunting within their service but give less clarity on the motives behind hunts, the hypothesis being validated, and when the hunt is deemed complete. Threat hunting tries to find attackers that evade security controls, which requires MDR providers that offer hunting to do so with a systematic, formal methodology.

So next time you think about hunting, consider the following and then consider which one of these two approaches will benefit/provide the greatest value for your organization in the long-term.

If you have questions or want to chat about threat hunting in your org, drop us a line.

References: