Threat intel · 12 MIN READ · AARON WALTON · JAN 15, 2026 · TAGS: Detections / Malware

TL;DR

- Gootloader malware is delivered to victims in a ZIP archive and the ZIP itself is designed to bypass detection.

- The ZIP archive is deliberately malformed causing many unarching tools to fail in analyzing it.

- However, defenders can take advantage of its unique format and behaviors to build detections.

The Gootloader developer has been involved in ransomware for a long time. Their role within ransomware has been initial access: getting the foot in the door. Once the malware runs on a system, they hand their access to someone else.

In being responsible for this job, the Gootloader developer has incentive to ensure that their malware receives a low detection score and can bypass most security tools. They’ve been very successful with this over the years. In years past, Gootloader malware made up 11% of all malware we saw bypassing other security tools.

As documented by others (Huntress and an independent researcher), Gootloader returned in November 2025 after a hiatus. According to Huntress, the developer is working again with the threat actor tracked as Vanilla Tempest: an actor currently leveraging Rhysida ransomware. The aforementioned reports cover how the malware is being dropped and the second stage of the malware; we’re going to discuss the first stage of the malware.

The first stage of the malware consists of a malformed ZIP archive, which can thwart some automated processes and human analysis. We’ll take a deep look at the ZIP archive itself and discuss how defenders can take advantage of its shape.

Zip it up

When a user downloads Gootloader malware, they download a JScript file compressed in a ZIP archive. The JScript, when executed, is responsible for kicking off the infection and spawning a PowerShell process which establishes persistence on the infected system—but the ZIP archive itself shouldn’t be ignored.

From 2021–2023, we observed the Gootloader developer using a unique ZIP archive. The ZIP archive contained abnormal characteristics, allowing us to consistently identify it as having been created by the Gootloader developer’s infrastructure. So when the campaign resumed, we investigated the archive again.

The characteristics of the latest version of the ZIP archive have changed, but it is again unique to the actor. The actor creates a malformed archive as an anti-analysis technique. That is, many unarchiving tools are not able to consistently extract it, but one critical unarchiving tool seems to work consistently and reliably: the default tool built into Windows systems. By being inaccessible to many specialized tools (such as 7zip and WinRAR) it prevents many automated workflows from analyzing the contents of the file, but by being accessible to the default Windows unarchiver, it ensures that the actor’s target audience (potential victims) can open and run the JScript.

Bottom line up front (this is a ZIP archive file format joke)

The following summarizes the abnormal features of Gootloader’s ZIP archive. In the deep dive, we’ll discuss the file format and illustrate how to observe the malformed features. The deep dive provides an educational resource, shows our findings, and supports our detection recommendations.

Gootloader’s ZIP archives have the following features:

- The file consists of 500–1,000 ZIP archives concatenated together. Because ZIP archives are read from the end of the file, the ZIP archive can still function properly. The number of ZIP archives concatenated together is random, and the ZIP archive itself is generated at the time of download.

-

- NOTE: We say the user downloads the malformed ZIP archive for convenience—what actually happens is a bit more exotic and won’t be analyzed in depth in this post. Essentially, the user receives an XOR encoded blob of data, which contains one ZIP archive. The blob is decoded and appended to itself until it meets a set size. This happens on the victim’s hosts via their web browser. This prevents defenders from detecting the ZIP when it’s passed over the network, but still delivers the hundreds of ZIP archives appended together. Randy McEoin discovered this mechanism and discussed it with us privately.

-

- The ZIP archive’s “End of Central Directory” file structure is truncated: two critical bytes are missing from the expected structure. This causes errors when some tools attempt to parse the End of Central Directory.

- For each of Gootloader’s ZIP archives generated, values in non-critical fields are randomized: fields such as “Disk Number” and “Number of Disks” are randomly assigned, causing some unarchiving tools to expect a sequence of ZIP archives which don’t exist.

The random number of files concatenated together and the randomized values in specific fields are a defense-evasion technique called “hashbusting.” In practice, every user who downloads a ZIP file from Gootloader’s infrastructure will receive a unique ZIP file, so looking for that hash in other environments is futile. The Gootloader developer uses hashbusting for the ZIP archive and for the JScript file contained in the archive.

As a result of hashbusting, defenders must create more dynamic ways of identifying these abnormal files on disk and ensuring dynamic detections can identify malicious activity if the file is run, as it’s highly unlikely to get flagged by antivirus or EDR based on static detection. See the final section of this report for detection methodologies and suggestions for detection.

Deep dive

What good looks like

In this section, we’ll give an overview of what a normal ZIP archive is and look at a normal archive in analysis tools. We’ll go into a fair amount of detail since file formats aren’t everyone’s specialty and some readers are most likely new to thinking about file formats.

The normal ZIP archive

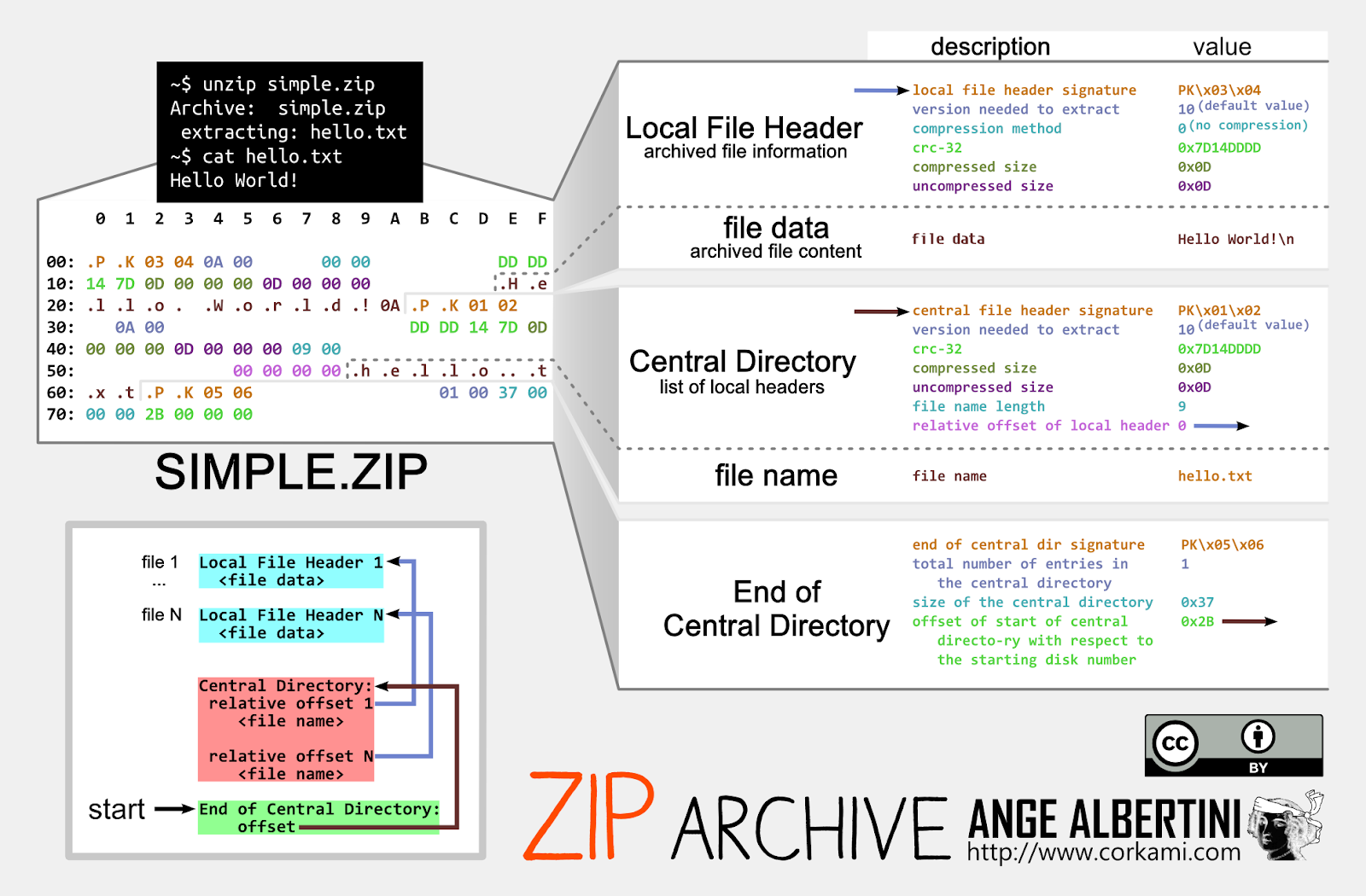

The following is a poster created by Ange Albertini breaking down a simple ZIP archive’s file structure. In his example, the ZIP archive under review contains a simple text file that reads “Hello World!” The top left of the poster shows the hexadecimal content of the ZIP archive and the right side explains the color-coding showing the structures that make up the file format.

The file format contains three main structures: a local file header containing metadata just before each compressed file, a central directory indicating where the files are located, and a section called “End of Central Directory”, which points to the where the directory itself can be found. When the archive is read by an unarchiving tool, it starts with the End of Central Directory as illustrated in the poster in the bottom left corner.

Gootloader’s ZIP, if it were normal

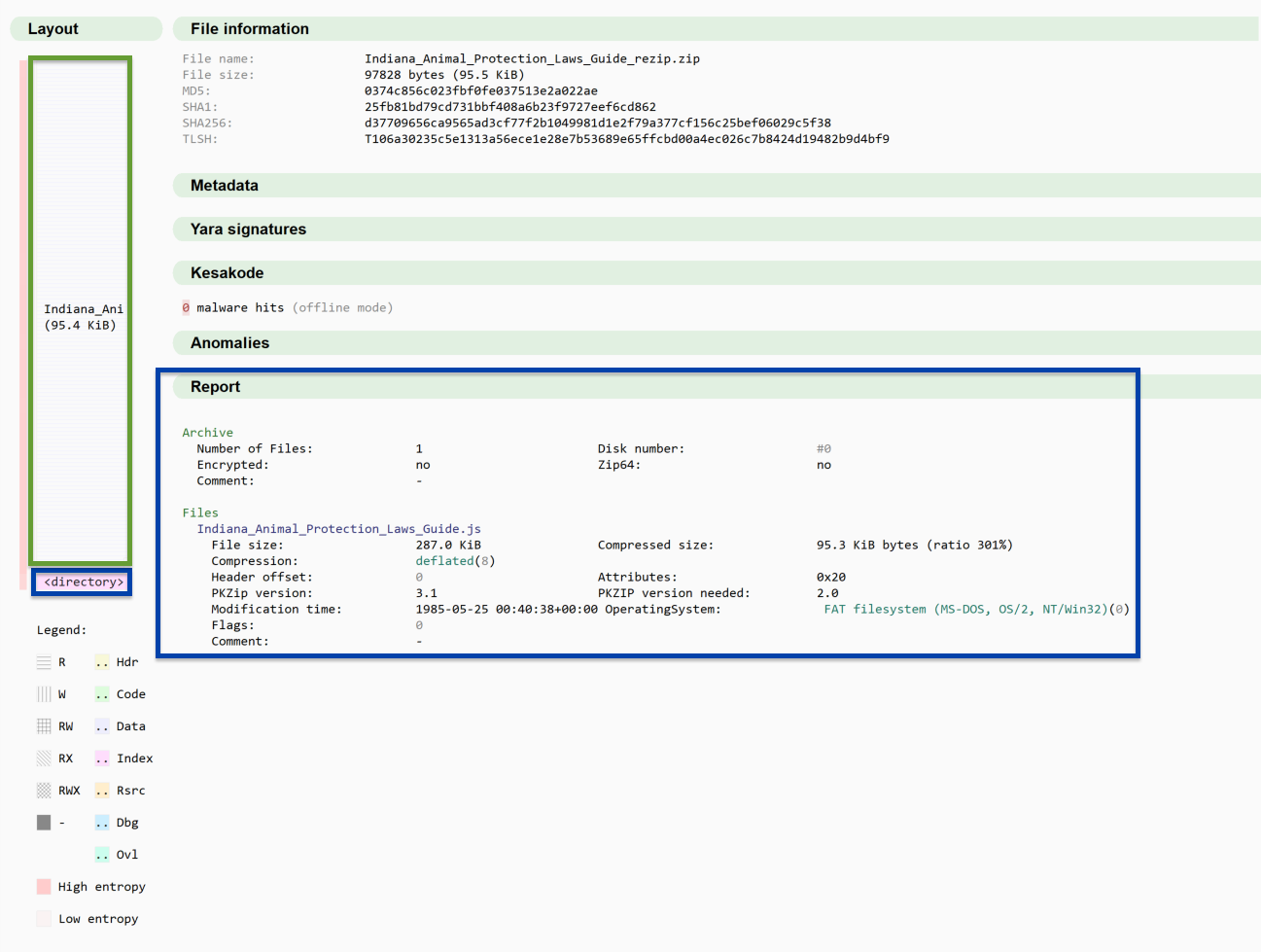

Below, we’ve unzipped the Gootloader JScript file and re-zipped it into an archive. We’ll use two tools to visualize the ZIP archive’s structure: Malcat and ImHex. This ZIP archive only contains one file, so the structure is very simple and identical to the file format poster above.

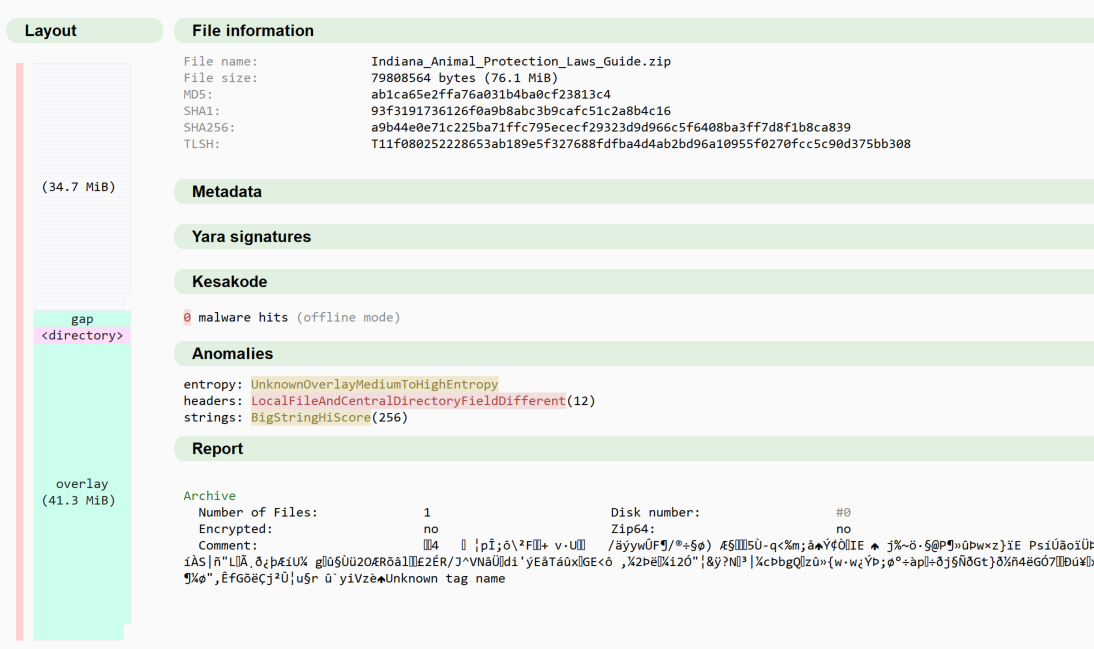

The following is an image of the archive loaded into Malcat. On the left is the layout, where Malcat identifies the Central Directory and End of Central Directory at the end of the file (simply labeled “directory”) and the singular file within the ZIP archive: Indiana_Animal_Protection_Laws_Guide.JS. In this image, Malcat also produces a report (highlighted in blue) that summarizes the details of the ZIP archive’s central directory.

The directory indicates that the archive contains one file, is not encrypted, has no comments, isn’t separated across floppy disks, and isn’t using Zip64.

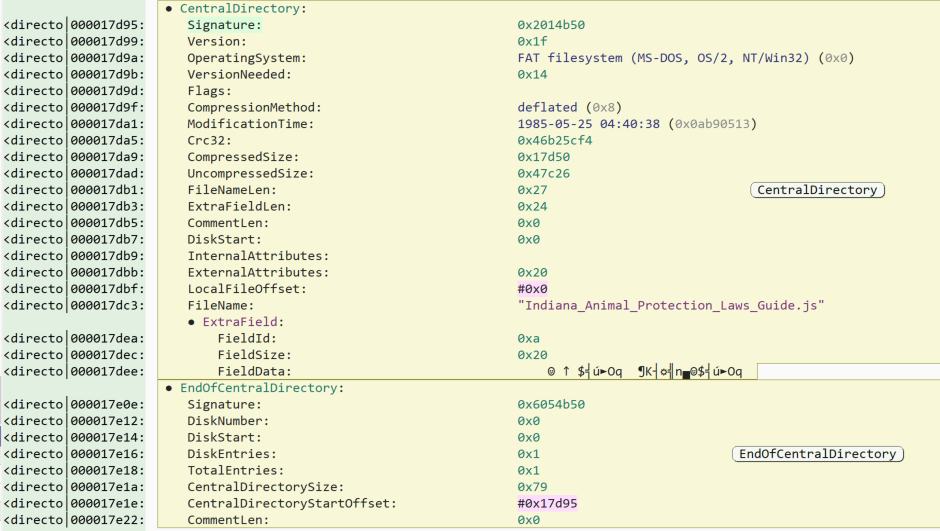

Within Malcat, we can view the Central Directory in the “structure view” which explains the values based on documented standards for the file format.

These high level views and the structural view are valuable for readability. However, it’s important to know and understand that these values are just a series of hexadecimal values. The image below is the hexadecimal values as they appear from Malcat. In this view, Malcat highlights the Central Directory and End of Central Directory structures as defined by the standards.

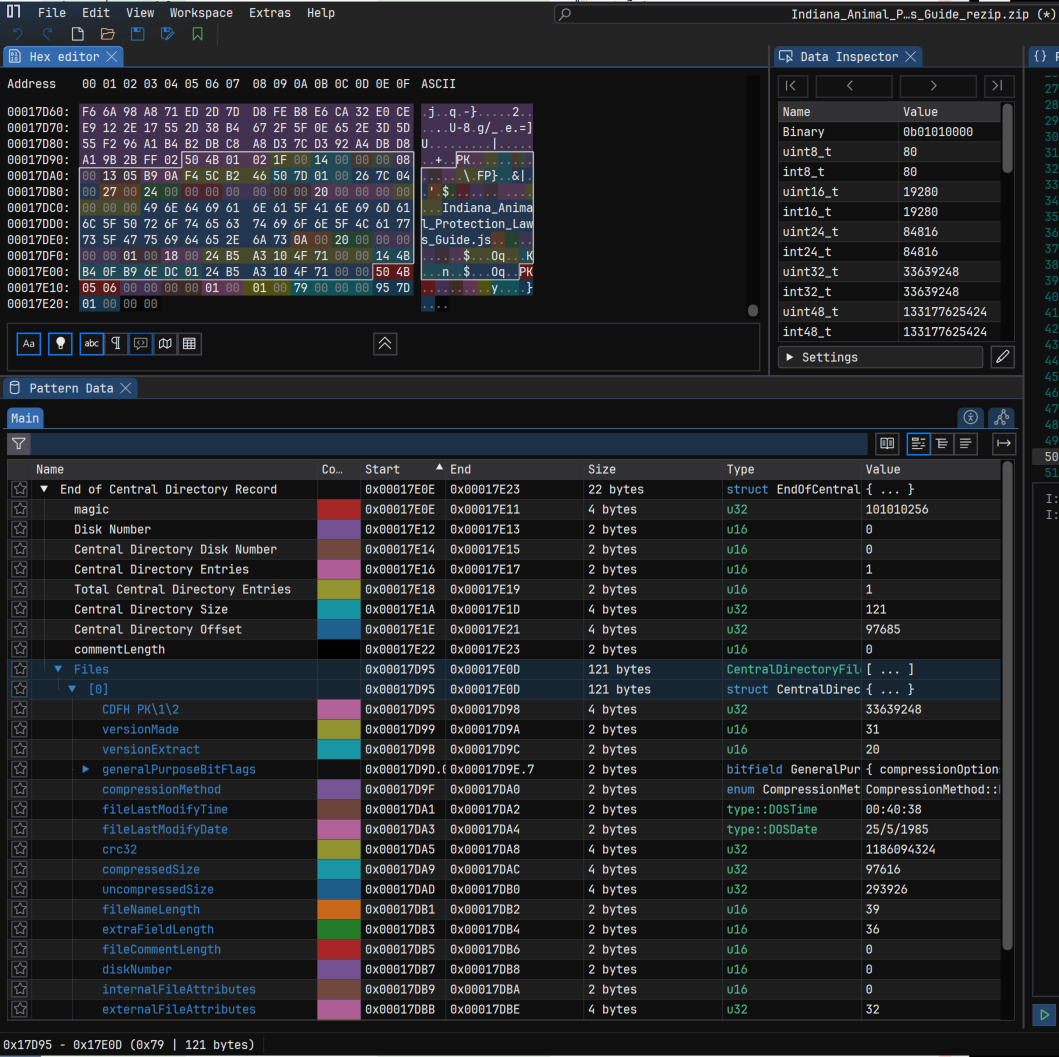

When analyzing files at this level we also use dedicated hex editing tools. Tools like ImHex and 010 Editor allow the user to set a pattern to identify the major sections, as well as the individual components of those sections. In the image below, a pattern based on the ZIP archive standard is used in ImHex. With the pattern, ImHex highlights each part of the structure. The pattern also generates a table with the parts broken down. In the image, the Central Directory is selected and highlighted in the hexadecimal view.

Based on these tools we can summarize some of the following key features of this ZIP archive:

- The ZIP archive contains one file.

- The file is 287 KB uncompressed.

- When compressed, the one file is 95.3 KB in size.

In these examples, the ZIP archive follows the standard. Next we’ll look at the ZIP a user downloads from websites infected by the Gootloader developer.

What bad looks like

The following ZIP archive is the original ZIP that contained the JScript file “Indiana_Animal_Protection_Laws_Guide.js”.

Immediately, we notice a lot of anomalies. First, the total size of the ZIP is 76.1MB in size: 819 times larger than the normal ZIP archive we just reviewed. Yet, if the file is extracted from the archive, the file is only 287KB.

Second, we also see a very different structure in Malcat’s layout diagram, as pictured above. According to it, the file consists of 34.7MB of compressed data, followed by a gap, the Central Directory, and then an overlay—essentially data appended to the end of a file outside of the file’s normal structure. This is all abnormal. This is indicative of Malcat struggling to make sense of the file.

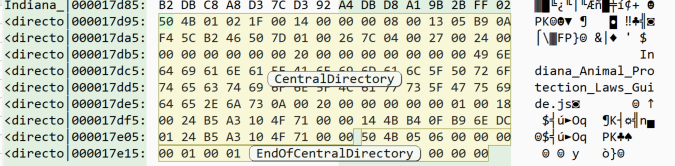

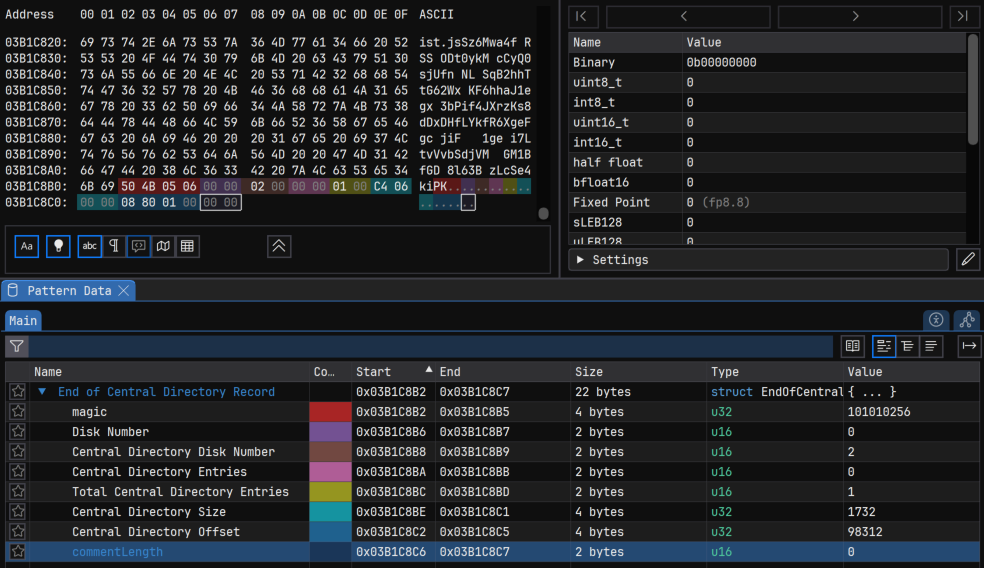

In investigating the parsing failure, we find the End of Central Directory is malformed in this ZIP file. When we compare just the raw bytes between the ZIP files we see an immediate problem: they aren’t the same length, and not all parts of the structure are accounted for.

|

Well-formed |

504B0506000000000100010079000000957D01000000 |

|

Malformed |

504B05060000000000000100F2050000F8810100 |

The End of Central Directory has fields that must exist and be the expected number of bytes, even if they’re empty. In this case, the “Comment Length” field is missing. By adding these back in using a hex editor, the parser can now identify the End of Central Directory. However, this doesn’t solve all the problems.

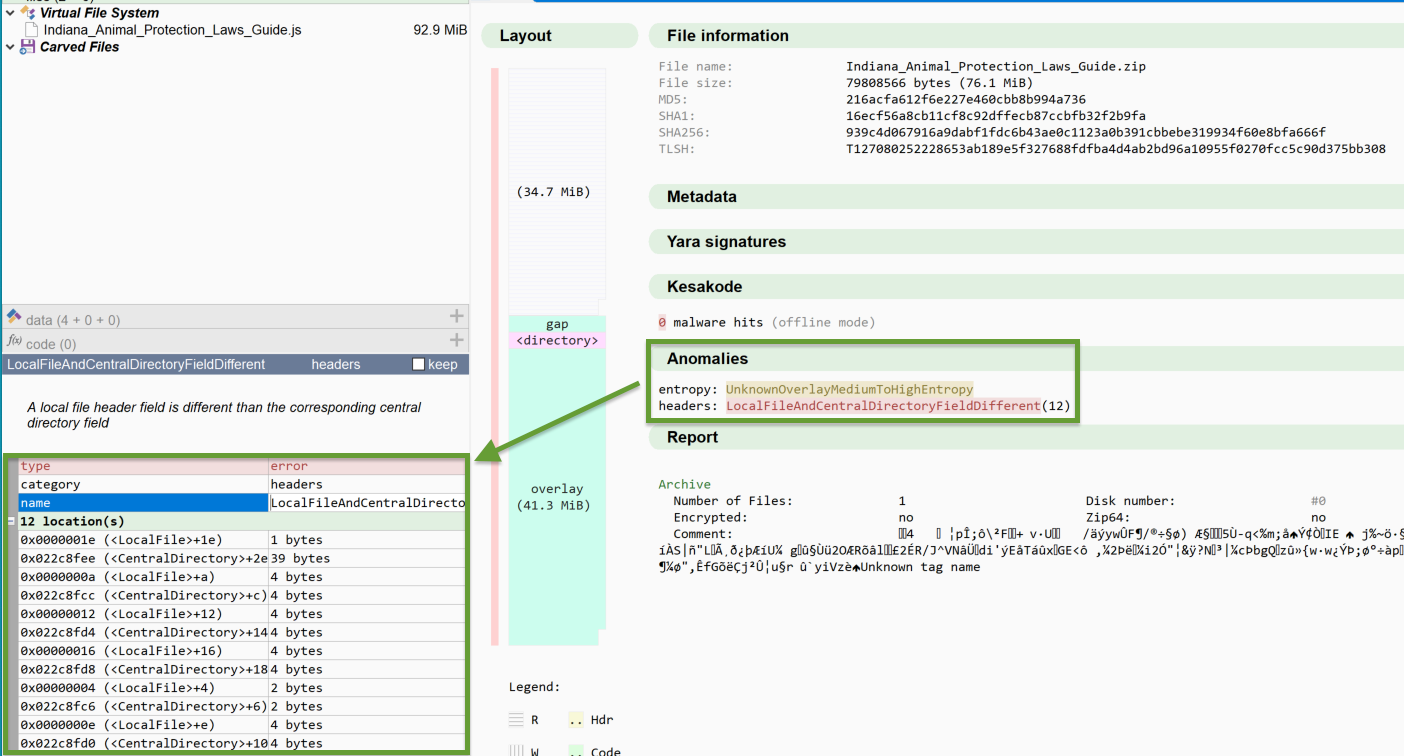

Malcat’s anomaly engine highlighted one of the other issues with the ZIP archives: multiple elements of the local file’s metadata differ from what’s in the central directory. That is, both the local file header and the central directory should contain identical information about the file, but in this file, that’s not the case.

In this example, the following fields mismatch:

- Version to extract

- Modification time

- CRC32 (cyclic redundancy check; that is, a hashing method to help detect errors)

- Compressed size

- Uncompressed size

- File name length in bytes

- File name

The following table shows the mismatches in this file. We observed these fields mismatch consistently across files we reviewed—and some values such as “version to extract” and “modification time” are seemingly randomized.

| Structure | Version to extract | Modification time | CRC32 | Compressed size | Uncompressed size | File name length | File name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Local file header |

0x34 | 2010-02-13 19:05:12 | 0x34 | 36 KB (0x22b1390) | 89 KB (0x555b776) | 0x1 | / |

|

Central Directory |

0x14 | 2024-05-06 20:15:38 | 0x1a20400c | 21 KB (0x1425f8c) | 97 KB (0x5ceb041) | 0x27 | Indiana_Animal_Protection_Laws_Guide.js |

For most unarchivers, the mismatch of the CRC32 would be enough to indicate corruption of the file contents and cause decompression to fail, so it’s unclear which specific elements cause specific unarchivers to fail.

More than one

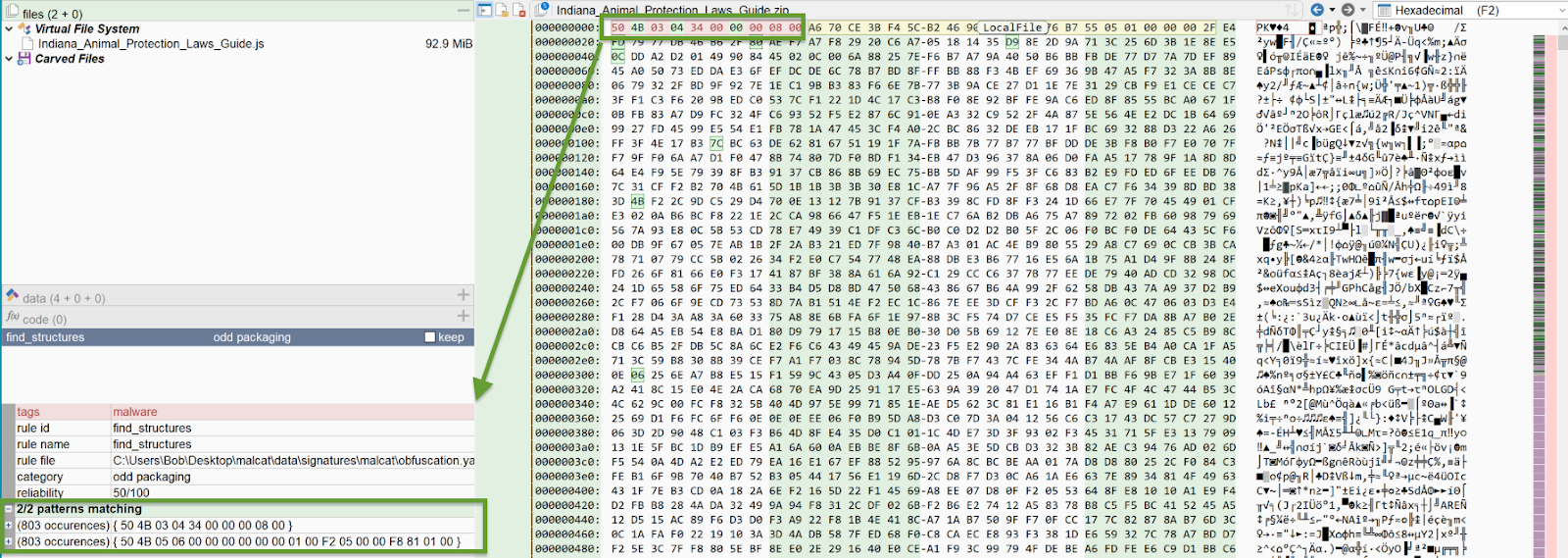

By creating a YARA rule looking for static features of the Local File header and End of Central Directory, we find that the two structures aren’t each occurring one time in this file as expected. They both occurred 803 times.

Since the actor appends identical ZIP archives together, the End of Central Directory always points to the same hard-coded address for the Central Directory, allowing the directory to point to the expected file. This allows the ZIP to function despite the random size.

From anti-analysis to action

There is much more that could be said about the ZIP archive, but there’s an important question to answer first. What can we do with what we know already?

Detecting the ZIP archive

We can use what we know to detect Gootloader’s malformed ZIP archives. The following YARA rule can consistently identify the current ZIP archives (November 11 to the time of this publication; however, the methodology for creating these archives may change once this report is public). The YARA rule looks for specific ZIP characteristics in the local file header at the start of the file, more than 100 occurrences of the same local file header, and more than 100 occurrences of the End of Central Directory with specific characteristics.

rule gootloader_zip_archive_2025_11_17 : malware {

meta:

name = “gootloader_zip_archive”

description = “Detects unique ZIP archive format used by Gootloader”

created = “2025-11-17”

reliability = 100

tlp = “TLP:CLEAR”

sample = “b05eb7a367b5b86f8527af7b14e97b311580a8ff73f27eaa1fb793abb902dc6e”

strings:

$zip_record_and_attacker_zip_parameters_hex = { 50 4B 03 04 ?? 00 00 00 08 00 } // check file header

$end_of_central_directory = { 50 4B 05 06 0? 00 0? 00 00 00 01 00 ?? ?? 00 00 ?? ?? ?? 00 }

condition:

$zip_record_and_attacker_zip_parameters_hex at 0

and #zip_record_and_attacker_zip_parameters_hex > 100

and #end_of_central_directory > 100

}

This YARA rule is on our GitHub.

We chose to use a YARA rule for this because it helps you when investigating to know for certain this tactic was used. The malicious JScript is more complex to detect: similar to the ZIP archive, it has a large deal of randomness, and it’s also disguised to look benign. The Gootloader developer uses a benign JScript file, which is usually 10,000 lines long and hides 100 lines of malicious code within it. Reviewing the script manually—or even in a sandbox environment—may not easily expose its functionality. However, detecting the ZIP file provides analysts a pivot point to identify the malware in the environment and start investigating further.

Running from the ZIP

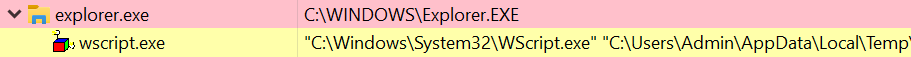

After a user downloads the ZIP archive, they’re likely to double-click it. If the Windows unarchiver is their default unarchiver, it’ll open the ZIP folder in File Explorer. Most users will double-click the JScript file, which by default will run the JScript using Windows Script Host (WScript). Since the file isn’t explicitly extracted from the ZIP and saved to disk, WScript will execute the JScript from a temporary folder. The process tree will look as follows:

This happens because when a ZIP archive is opened, a temporary folder is created containing the ZIP archive contents. However, this provides a detection opportunity because the majority of users shouldn’t be running JScript files from a ZIP archive. The detection should look for Wscript executing a JScript file from the “AppData\Local\Temp” folder.

This also raises the question, should your users be running JScript files directly at all? Over the years, we’ve consistently seen malware bypass other security defenses by being delivered as a JScript file. They can do this because the JScript file itself is just a text file. However, by default, if a user double-clicks a JScript file, it’ll be executed with WScript. This is due to a Windows setting indicating that the default program to open JScript files is WScript. This default setting can be changed with a Group Policy Object (GPO). We recommend changing the default program to Notepad, which prevents execution of the file when double-clicked.

Note: If the default is changed, power users can still execute JScript files if they need to.

Beyond the ZIP archive

As documented in the Gootloader is Back post, the current JScript does the following:

- Creates an .LNK file in the user’s Startup folder (C:\Users\<username>\AppData\Roaming\Microsoft\Windows\Start Menu\Programs\Startup). Files in this directory are run when the computer starts up.

- The .LNK points to another .LNK in a random directory chosen by the JScript.

- A second JScript file is dropped in that same random directory and is pointed at by the .LNK file.

After the user double-clicks the JScript—and after every computer restart—the .LNK will execute the second .LNK, which in turn executes the second JScript file. This is another detection opportunity.

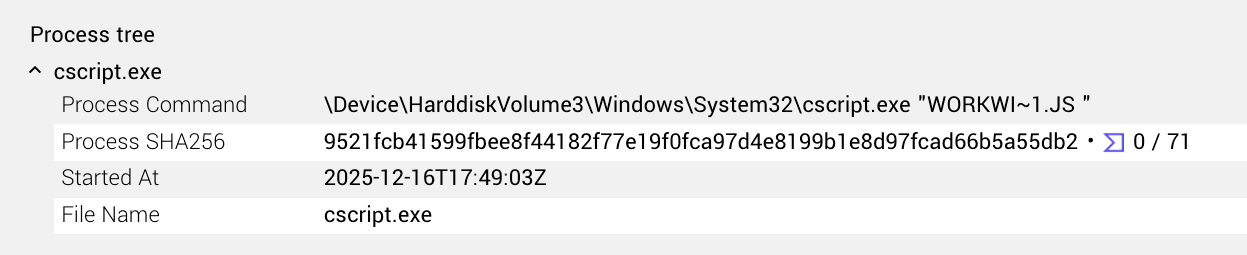

When the .LNK file executes the JScript file, it does so with CScript and it runs from the same directory as the JScript file. As a result, the JScript is run with no directory specified. The JScript is also executed using a NTFS shortname. NTFS was developed in 1993 as part of Windows NT, and the short name is used for legacy systems that can’t handle longer file names, shortening them to six characters, followed by ‘~1’ in most circumstances. Features like NTFS shortnames have been with Windows for a long time, but their appearance is fairly rare, which gives us a detection opportunity. We recommend having a detection for CScript executing a JS file using a NTFS shortname.

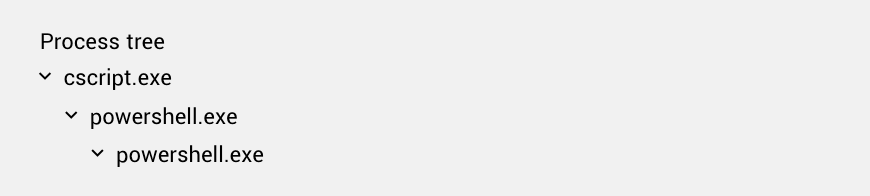

When executed, the CScript will spawn PowerShell, which is also highly unusual and worth a detection. The PowerShell in turn spawns a second PowerShell instance containing a heavily obfuscated command. We recommend a detection focusing on the process genealogy of Cscript spawning PowerShell.

Goot-bye and goot-riddance

Looking at the first stage of a Gootloader infection allows us to detect and prevent Gootloader at its earliest point. Over the years, we’ve seen the Gootloader developer change their malware time and time again, but by understanding the details of their campaign, we’re able to prevent them from getting a foothold within environments.

Copies of the first stage ZIP file can be found on MalwareBazaar with the Gootloader tag.

Gootloader defense summary

- Prevention and hardening

- Reassociate JScript extensions:

- Use Group Policy Objects (GPO) to change the default “Open with” association for .js and .jse files from the Windows Script Host (WScript.exe) to Notepad. This ensures that if a user double-clicks a malicious script, it opens as a text file rather than executing.

- Attack surface reduction:

- If JScript is not required for business operations, consider blocking wscript.exe and cscript.exe from executing downloaded content or restricting them entirely.

- Reassociate JScript extensions:

- Detection opportunities

- Detection should focus on the abnormal behavior of the ZIP archives and the subsequent process execution chain.

- Monitor for wscript.exe executing a .js file located within the AppData\Local\Temp directory.

- Monitor for the creation of .LNK files in the user’s Startup folder pointing to scripts in non-standard directories.

- Flag instances where cscript.exe executes a .js file using legacy NTFS shortnames (e.g., FILENA~1.js).

- Alert on the specific process tree: cscript.exe → powershell.exe

- Detection should focus on the abnormal behavior of the ZIP archives and the subsequent process execution chain.