Threat intel · 3 MIN READ · BEN NAHORNEY AND AARON WALTON · NOV 6, 2025 · TAGS: Guidance

TL;DR

- In this blog we take a look back at critical activity we investigated during the quarter.

- One of the most prolific threat groups was BaoLoader, which comprised 13% of the non-targeted malware we saw this quarter.

- The post examines the threat posed by the group, looks at similar campaigns, and discusses the implications.

Welcome to part two of our Q3 2025 threat report! (Missed part one? You can find it here.)

This quarter we shed light on a threat actor that’s been lurking behind the label of potentially unwanted programs (PUP). This centers on the activity of the BaoLoader malware. Over the course of two blogs, we took a look at new activity from their software—which suggested not everything was as it seemed—and then dove deeper, documenting how the campaign had developed over the years.

Let’s take a step back to examine the threat posed by the group as a whole, look at a few similar campaigns, and discuss the long-term implications of this activity.

BaoLoader: Malicious fillings in a wholesome wrapper

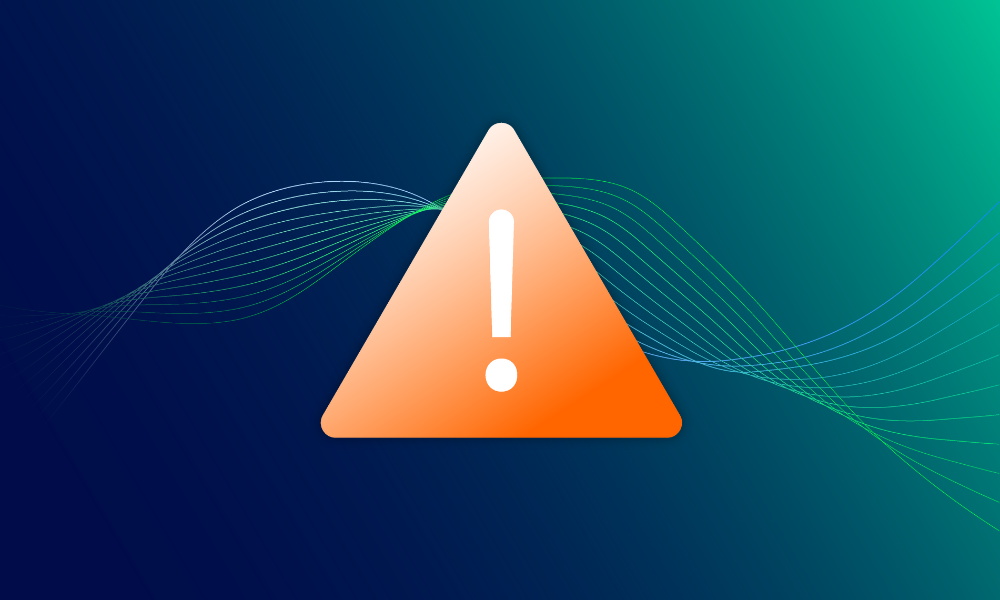

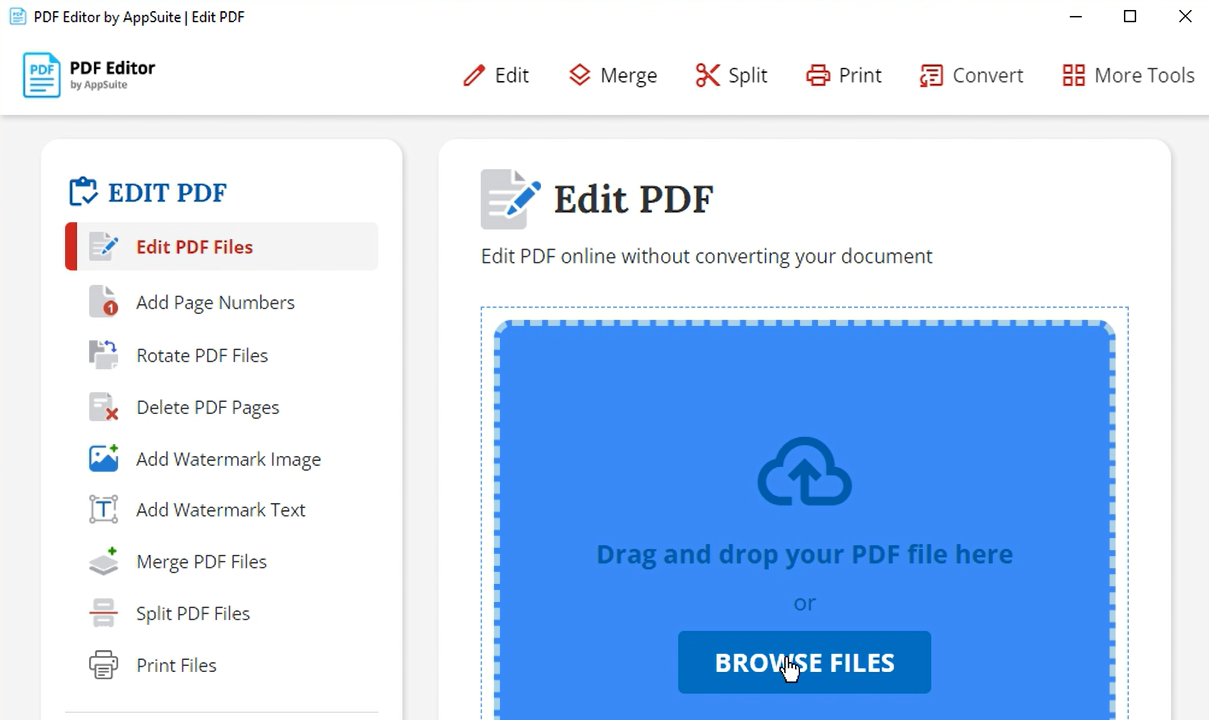

Our threat researchers exposed a long-running operation during the quarter that involves productivity applications bundled with malicious functionality. Historically, their various software had been treated as PUPs—software applications not entirely seen as malicious, but aren’t something you’d necessarily want in your environment. However, our analysis (and the analysis of others) found that the apps set up a backdoor when installed.

The applications were business utilities a user might download in a pinch or by accident, such as PDF editors, tools to locate manuals, and browsers. While the apps generally performed their stated function, the backdoor established by the software allowed the operator to execute arbitrary commands. The typical use by the operator was to install applications as part of affiliate fraud scheme, earning money for each install. Installed software ranged from browser extensions to residential proxies. However, they caused alarm when they began executing PowerShell to enumerate antivirus installed on systems, and even installing additional applications of their own.

Our investigation, conducted in collaboration with CertCentral.org, outlined the most recent activity was part of a long-running campaign by a team of threat actors who obtain code-signing certificates for use with their malware to make it appear more legitimate. The actors do this by leveraging dozens of companies from the US, Panama, and Malaysia to request the certificates. By investigating the certificates used to sign files over the years, we were able to see how the campaign had developed.

As a result of our investigations, we identified the malware was prevalent across multiple industries and made up 13% of all non-targeted commodity-malware identified by our analysts. As we discussed in part one of this QTR, non-targeted malware was the most common threat vector seen on endpoints this quarter.

In contrast to the majority of malware we see, we haven’t observed the BaoLoader actors stealing credentials, deploying remote access tools (RATs), or performing destructive actions. Based on our research, this is because these aren’t the typical cybercriminals that target enterprises, looking for a large payout or ransom. While their main operation has been centered around affiliate fraud, the presence of an arbitrary backdoor introduces an unquantified risk that can’t be ignored—demonstrated by their willingness to execute PowerShell to check for the presence of antivirus software or drop additional files.

TamperedChef: Apps with secret ingredients

The use of functional, albeit dubious, applications brought broader awareness to other functional applications with their own secrets.

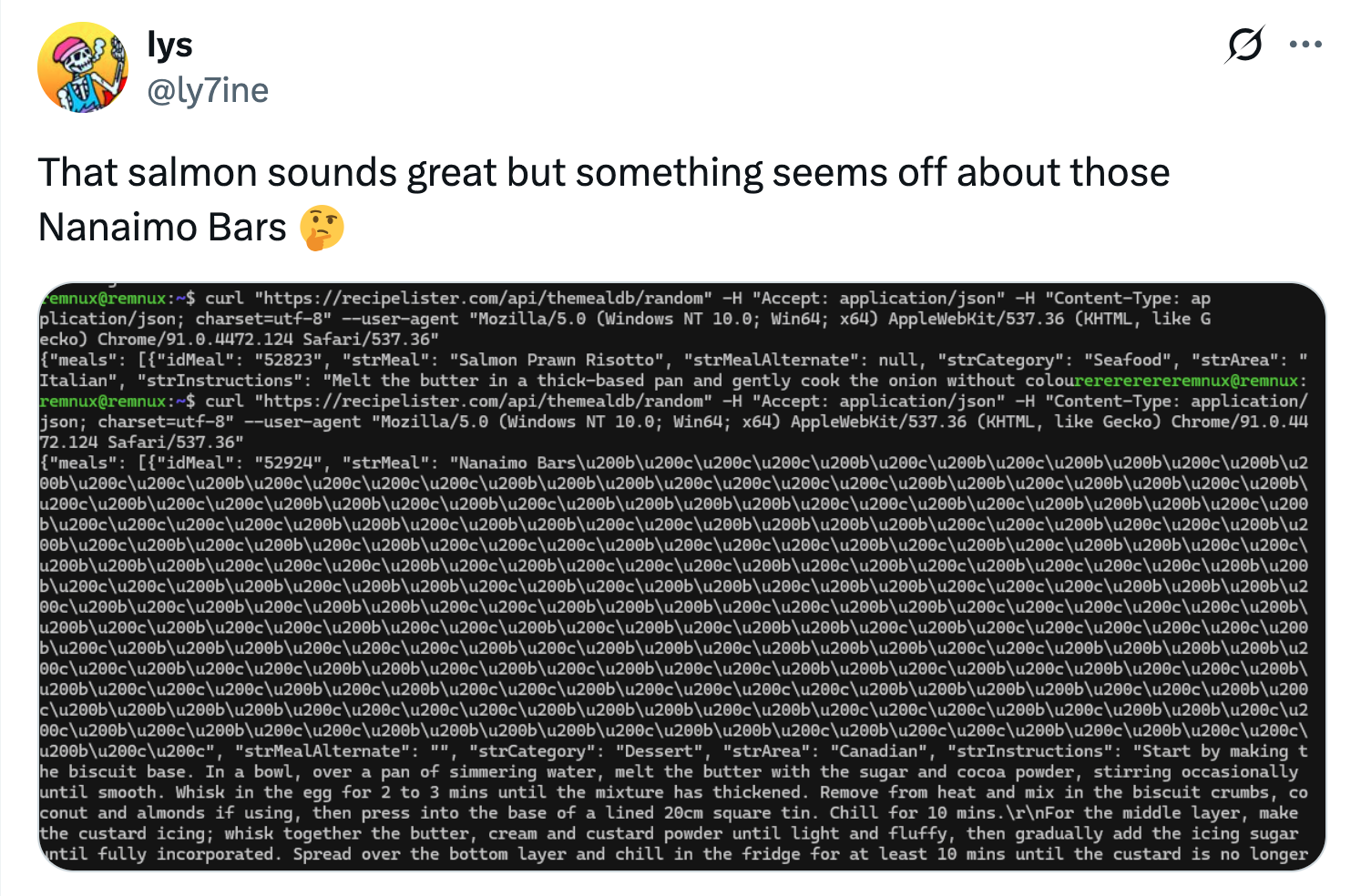

In addition to BaoLoader, a separate malware family was identified (jokingly called TamperedChef). This malware was a functional, but limited, recipe app. Some recipes contained hidden characters that could be decoded and decrypted by the app.

During our investigations, we found users often downloaded the malware through ads after the user looked for information about calendars. Despite being a recipe app, we found that the malware was surprisingly common, with more than 34,000 downloads.

After information was published about the malware and their code-signing certificates were revoked, the actor shifted to other fake applications, including a calendar app.

Their calendar app, Calendromatic, was also seen frequently throughout this quarter. Similar to their previous malware, the app passes hidden information with a custom encoding scheme as documented by Guidepoint, replacing standard characters in calendar entries with homoglyphs—similar-looking characters with different Unicode designations.

Too many cooks in the kitchen

Apart from BaoLoader and TamperedChef, we’ve seen many other examples of functional applications with backdoors and malicious capabilities. TrendMicro and GDATA suspect that this rise in trojanized, functional apps is due to AI/LLMs making app creation easier. With LLMs, cybercriminals can more easily create a decoy application that obscures the real intent of the software. As a result, we expect the grey area between malware and PUPs isn’t going anywhere anytime soon. Organizations will need to remain vigilant in terms of the types of applications users are allowed to install on their devices. We recommend using strict application control policies to prevent malicious files from being installed.

If there’s a gap in applications needed to carry out day-to-day business that are not available to them, it is important to identify sanctioned tools to enable them to carry out their responsibilities.